Olive's Journey With Her Twin

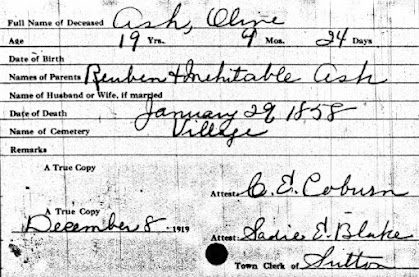

Olive Ash worked for a farmer, Mr. Beckwith, in Vermont, in the summer and fall of 1857. She was 19 years old, and she lived with the family during her employment. In the autumn of that year, Olive returned to her family home in Sutton.

On December 28, 1857, Olive and her twin sister, Olivia, left their home and went by rail to the home of their cousin, Levi M. Aldrich, in Bradford, ostensibly to visit his widowed mother. During the visit, Olive seemed to her family to be in normal health.

The sisters remained at Aldrich's home about two weeks, then said that they were going to meet some friends at the Fairlee depot for an excursion into New York or Massachusetts. Instead, when they arrived at Fairlee depot they took a wagon to the home and office of Dr. William Howard, about six miles north of the depot and three miles south of Bradford.

The Dreadful Telegram

On Friday, January 29, 1858, Olive's mother, Mahitable, got a telegram telling her to come to Howard's home. She quickly complied, and was there when her daughter died at about 6 in the evening. Dr. Howard got a coffin for Olive, and the twins' mother took the body by train to Sutton.

The Investigation

On February 3, Olive's body was exhumed for an autopsy, which was performed by Dr. Frost and witnessed by Dr. Bliss, Dr. Carpenter, and others unnamed. Frost found evidence of recent pregnancy as well as signs of instrumentation and damage to the cervix. Dr. Frost believed that Olive had hemorrhaged due to the damage to her cervix. He removed and preserved her uterus. Another physician examined the uterus and concluded that the placenta had been retained for some time after the abortion, and that this retained placenta would also cause hemorrhage.

Olivia Testifies

In the trial of Dr. Howard, Olivia testified that she knew her sister was pregnant and had accompanied her on the journey knowing that Olive was planning to get an abortion. Olivia said that Daniel Beckwith, the grown son of the farmer Olive had worked for, met them at their cousin's house, and he gave them the information on where to go and who to see for the abortion.

From Olivia's testimony, the sisters arrived at Dr. Howard's house and informed him that Olive was about six months pregnant. He spoke to the sisters and indicated that he wanted to consult with Daniel Beckwith before deciding if he was going to proceed with an abortion. The sisters remained at Dr. Howard's house for a few days until Olive got a letter from Beckwith, and she read part of it to Dr. Howard. He then agreed to perform the abortion for a sum of $100. (Over $3,600 in 2023)

Dr. Howard told the sisters that the process would take three or four weeks. He gave Olive a concoction to drink two or three times. On the Friday the week after the sisters' arrival, Dr. Howard performed some sort of procedure on Olive as she lay on the bed in the room the twins shared. Olivia was permitted to remain with her sister during this procedure. She said that Dr. Howard used two or three of the three or four instruments he had at hand. Olive was in pain during the procedure, which took two or more hours, and resulted in a gush of fluid.

The following day, Dr. Howard performed another, similar, procedure on Olive, who clutched her sister's hand and reported great pain. Olive bled profusely. After this second operation, Olive kept to her bed.

That night, Dr. Howard performed yet another procedure, very painful for Olive to endure. This time he used instruments then reached in with his hand and pulled out a fetus, which Olivia reported as being about two-thirds the size of a newborn. Dr. Howard removed the fetus from the room, and Olivia never saw it again.

Olive bled after this, but not profusely. Afterward her behavior struck Olivia as violent and irrational.

Other Testimony

A girl named Margaret Kelley, who lived at Dr. Howard's house, testified that Olivia had laundered her sister's bloody clothing while at the doctor's house.

Bloody items were introduced into evidence, including two chemises and a small quilt or pad. The witness, Mrs. Wilson, who produced the evidence indicated that she'd found these things hidden in the rafters of the house when she was cleaning in the fall of 1858.

Mrs. Wilson also said that about two weeks after Dr. Howard's arrest, she saw one of Dr. Howard's dogs come out from underneath the office privy with something in its mouth. She made the dog drop what it was carrying and discovered it to be a fetus of about four or five months, in a state of decomposition. While she was looking at the fetus, another of the doctor's dogs snatched the fetus up and ran off with it. The dogs, she testified, had been digging at the privy for some time before retrieving the fetus. Mrs. Wilson's description of the fetus she'd seen the dogs with was similar in size to the fetus Olivia had described taken from her sister. Olivia had also testified to having seen a number of fetuses of various sizes preserved in containers in Dr. Howard's premises.

Defense Witness

The defense presented a witness named Susan Squires, who was staying at Dr. Howards from January 23 until after Olive's death. She said that the Thursday before Olive's death, she had spoken with Olive while Olivia was eating lunch. Susan said that Olive told her that she didn't expect to live, that she'd taken poisons before coming to Dr. Howard, that Dr. Howard was not to blame in her death but had done everything in his power to help her. Susan said that Olive seemed rational at the time, but that by Friday morning Olive seemed to have lost her reason.

On cross examination, Susan indicated that she had stayed at Dr. Howard's off and on for two years, to do sewing and to receive medications. She indicated that on Thursday afternoon, at about 4:00 Friday morning Olive managed to kick the footboard off the bed, prompting Olivia to summon Susan and a Mrs. Green into the room. Olive complained of being tired and continued to thrash and kick for a short time before settling down.

Mrs. Green was brought as a witness. She said that she had gone to Dr. Howard's on Tuesday afternoon and remained there a week visiting the doctor's wife. She first saw Olive on Wednesday morning, when Olivia had summoned her to help attend to Olive, who was trembling, delirious, and bleeding from the nose. Mrs. Green also went to Olive during the episode when she'd kicked the footboard off the bed. She'd helped the others restrain Olive. Mrs. Green testified that Olive never revived enough to speak after that.

Outcome

Dr. Howard's witnessed attempted to show that Howard was treating Olive for a miscarriage. Dr. Howard was nevertheless convicted.