Reports on death of Evelyn Dudley, age 38, indicate that she was treated at Friendship Medical Center in Chicago on March 16, 1973. Later, at home, she collapsed in the driveway. She was taken to a hospital, where attempts to save her failed.

Her death was due to shock, hemorrhage from a ruptured cervix and vagina, from "remote abortion." T.R. Mason Howard

(pictured) stated that Evelyn was treated at Friendship for infection

sustained in an abortion in Detroit. But Evelyn's brother stated that

she had come to Chicago specifically to have the abortion.

Julia Rogers and Dorothy Brown also died after abortions at Friendship Medical Center.

Her death was due to shock, hemorrhage from a ruptured cervix and vagina, from "remote abortion." T.R. Mason Howard

(pictured) stated that Evelyn was treated at Friendship for infection

sustained in an abortion in Detroit. But Evelyn's brother stated that

she had come to Chicago specifically to have the abortion.

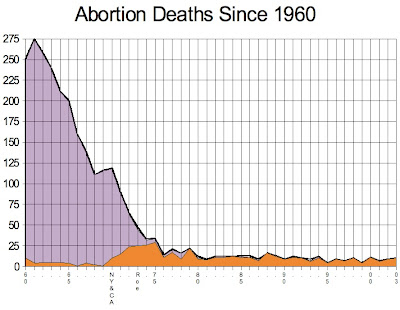

Julia Rogers and Dorothy Brown also died after abortions at Friendship Medical Center.As you can see from the graph below, abortion deaths were falling dramatically before legalization. This steep fall had been in place for decades. To argue that legalization lowered abortion mortality simply isn't supported by the data.

On March 16, 1924, 35-year-old Selma Hedlund died in Chicago's Jefferson Park Hospital (pictured) from complications of an abortion performed that day. The sources says that she died at the crime scene. Nobody was ever positively identified as the abortionist. However, a Carl Carlson, indicated as a person known to Selma, was arrested as an accomplice.

On March 16, 1915, 19-year-old saleslady Hazel Wilcox died at a Chicago home from sepsis caused by an abortion perpetrated that day by midwife Julia Patera. Patera was held by the coroner on March 20 but the case never went to trial, despite the fact that Elinora Cassidy had died only the previous day after identifying Patera as her abortionist.

On that same day, 26-year-old homemaker Hazel Carr died in her Chicago home from an abortion performed by an unknown perpetrator.

Note, please, that with overall public health issues such as doctors not using proper aseptic techniques, lack of access to blood transfusions and antibiotics, and overall poor health to begin with, there was likely little difference between the performance of a legal abortion and illegal practice, and the aftercare for either type of abortion was probably equally unlikely to do the woman much, if any, good. In fact, due to improvements in addressing these problems, maternal mortality in general (and abortion mortality with it) fell dramatically in the 20th Century, decades before Roe vs. Wade legalized abortion across America.

Harriet "Hattie" Reece, a 25-year-old primary school teacher in Browning, Illinois, died March 16, 1899. The finger pointed at Dr. James W. Aiken. Hattie had consulted with a doctor two months prior to her death. She did have some health problems, but this doctor recommended continuing the pregnancy rather than taking the risk of an abortion. Hattie, however, was concerned about the effect being pregnant would have on her teaching career. She made inquiries and ended up corresponding with Aiken, who assured her that he could get her safely through an abortion. Hattie's husband, Frank, was against the idea of an abortion but said he'd agree to one if it was necessary for Hattie's well-being, but he had no faith in Dr. Aiken and refused to participate in any way. Hattie used her salary to travel to Tennessee to have her abortion. She took ill and sent for Frank, who found her in ill health, with Aiken saying that Hattie needed an abortion for her safety. Frank went back to Hattie's room, begged her forgiveness for having been harsh with her, and returned home.He got a telegram from his wife saying that she was worse and to come at once. When Frank arrived, Aiken told him that Hattie was dying and that he'd sent for her father. Aiken told Frank that "he had told the people Mrs. Reece had died of peritonitis. That was the story he had been telling and we must both stick to it as I was in it as deep as he." Frank told Aiken that he'd tell the truth, and went to speak with his wife. She told Frank that the abotion had been performed on Saturday (most likely March 4) with blunt instruments, and that she had expelled the dead baby on Wednesday (most likely March 8). Aiken had put the baby in his pocket and left with it. She recanted her story shortly before her death. Aiken seemed to be a bit of a George Tiller precursor -- somebody who would find a "life of the mother" case in any pregnancy. But unlike Tiller, Aiken couldn't just buy his way out of trouble. He was found guilty and sentenced to fifteen years.

On March 16, 1869, Magdalena Philippi died of complications of an abortion performed on March 11, evidently by a Dr. Gabriel Wolff, who continued to attend to her as she sickened and died. Although Magdalena was four or five months pregnant, prosecutors had no way of proving that she had felt movement in the fetus, so they could not prosecute Dr. Wolff. The next day, a bill was introduced in Albany to eliminate the quickening distinction in prosecuting abortion cases. This would make it easier to prosecute abortionists like Wolff. Magdalena's abortion was typical of illegal abortions in that it was performed by a physician.

No comments:

Post a Comment