On August 31, 1910, Mrs. Ellen Shirah, a 34-year-old Irish immigrant and mother of two, died in Augustana Hospital in Chicago that had been perpetrated in her home about two weeks prior to her death. The coroner's jury determined that a doctor had been responsible but did not identify him or her by name.

I've been unable to learn anything more about Ellen's death.

Monday, August 31, 2020

Sunday, August 30, 2020

A YouTube Story Confirmed

I stumbled across a video about a self-induced abortion death -- one I was able to verify by searching for a death certificate. Winifred "Win" Mayer died on April 18, 1944, at around 2:00 in the afternoon. Her death certificate attributes her death to shock "due to attempt at criminal abortion self inflected." She was in the second month of her pregnancy. The autopsy showed cuts in her uterus, hemorrhage, and congestion of her lungs, liver, and kidneys.

According to the YouTube video, Win was living in military housing in Virginia with her husband and two small children. Her husband, Eddie, worked for the government was about to be deployed overseas for an undetermined amount of time and Win didn't feel prepared to care for a third child while he was away. She already had a son, Peter, who was not quite three years old and a 10-month-old baby girl, Judy. Win was college educated and financially comfortable, according to her granddaughter.

Win's mother, her granddaughter says, was a nurse in New York. Win travelled to New York to use her mother's connections with doctors who performed criminal abortions. For some reason this arrangement fell through. Win's father, who was a doctor, refused to perpetrate the abortion. Win's daughter said that Win's French stepmother told her that women in France "take care of this themselves." Win returned to Virginia.

Whether she got specific instructions from her stepmother or another person or just came up with an approach on her own, Win put the children down for their naps, went into the bathroom, and attempted the abortion. Eddie came home after work and found her dead.

According to the YouTube video, Win was living in military housing in Virginia with her husband and two small children. Her husband, Eddie, worked for the government was about to be deployed overseas for an undetermined amount of time and Win didn't feel prepared to care for a third child while he was away. She already had a son, Peter, who was not quite three years old and a 10-month-old baby girl, Judy. Win was college educated and financially comfortable, according to her granddaughter.

Win's mother, her granddaughter says, was a nurse in New York. Win travelled to New York to use her mother's connections with doctors who performed criminal abortions. For some reason this arrangement fell through. Win's father, who was a doctor, refused to perpetrate the abortion. Win's daughter said that Win's French stepmother told her that women in France "take care of this themselves." Win returned to Virginia.

Whether she got specific instructions from her stepmother or another person or just came up with an approach on her own, Win put the children down for their naps, went into the bathroom, and attempted the abortion. Eddie came home after work and found her dead.

Saturday, August 29, 2020

August 29: Statutory Rape, Self-Induced in Pittsburgh, and Other Tragedies

Scant Information in Chicago, 1918 and 1925

On August 29, 1918, 23-year-old homemaker Mabel Johnston died at Chicago's Cook County Hospital of blood poisoning caused by an abortion involving Dr. Nathan Smedley and Dr. Emma Warren. Both were arrested and arraigned but the case evidently never went to trial.

On August 29, 1925, Katarzyna Tobiasz, age 31 or 32, died at Chicago's St. Mary's Hospital from an abortion performed on her that day. A woman whose name is spelled once as Barbara Kolur and elsewhere as Barbara Kar was held by the coroner on August 31 for Katarzyna's death. Kolur/Kar's profession is given as nurse or midwife. On July 5, 1927, she was indicted by a grand jury for felony murder in Katarzyna's death.

Self-Induced in Pittsburgh, 1926

On Wednesday, August 18, 1926, 22-year-old Myrtle Schall's friends and her fiancé, Bruce Armstrong, brought her to West Penn Hospital in Pittsburgh. She had been feverish and in pain for the past three weeks, and now she was in shock.

Bruce, who said he'd known Myrtle for six or seven years, knew only that his fiancée was terribly ill but didn't know why. Her mother, Alice Phillips, on the other hand, was able to tell the doctor more. Myrtle, she said, had attempted a self-induced abortion when her period had been two weeks later. At first her vaginal bleeding was a welcome sign that the abortion had worked, but when it continued for three weeks, accompanied by fever and pain, her family and friends had become concerned.

Myrtle had been perfectly well prior to inducing the abortion. Now she was vomiting and the doctors found her to be weak and anemic, with a rapid pulse and respiration and an alarming blood pressure of 136/100. In spite of all of the doctors' best efforts, Myrtle died from peritonitis at 8:15 p.m. on Sunday, August 29.

Myrtle's death certificate indicates that she was married to John Schall at the time of her death. Since Bruce was listened as the source of the information, and Myrtle was buried under her maiden name, it's likely that she and her husband were estranged and that she was awaiting a divorce so that she and Bruce could marry.

Abused and Abandoned in Chicago, 1927

In August of 1927, fifteen-year-old Florence Kruse, a junior at Lindblom High School, confessed to her parents that she was pregnant. Corwyn Lynch, an insurance adjuster in his early 20s, promised to marry Florence, then disappeared on August 15, telling his landlady that he was going to California. The deserted teen was disconsolate and began talking about suicide. That's when her parents, Louis and Amanda, reached out to Dr. James Aldrich, age 71.

On August 19, Mr. and Mrs. Kruse took Florence Aldrich's office at 5941 Normal Boulevard. After the abortion, Florence remained at Aldrich's office, attended by his wife. Her condition deteriorated over the ensuing week, and she was taken to Augustana Hospital. The doctors who treated her there reported the case to the coroner's office. A deputy spoke to Mr. Kruse, who admitted what they'd done.

Florence died on August 29. Deputy Coroner Joseph Kveton conducted an inquest at the Reilly undertaking establishment. After the funeral he had the girl's parents, Florence's parents, charged as accessories before and after the fact.

Mrs. Kruse wasn't home when police went to arrest her but was reportedly ill at another location. Mr. Kruse, evidently unable to raise the $5,000 bond, sat in a jail cell and threatened to kill Lynch.

The three parties in Chicago were released after the coroner's jury was unable to confirm that Aldrich had performed the abortion. The coroner recommended that Lynch be charged with murder.

I've been unable to learn anything more about the case.

Filthy and Substandard in Chicago, 1987

Diane Watson was 27 years old, a mother of two, when she went to Hedd Surgi-Center in Chicago for a safe and legal abortion on August 29, 1987. Although Diane was over 12 weeks pregnant, Rudolph Moragne proceeded with the abortion, in violation of state regulations prohibiting outpatient abortions after 12 weeks. He ended up hitting a vein when injecting anesthetics. Diane had seizures and went into cardiac arrest. Moragne and the other physicians present -- Henry Pimentel, Ester Pimentel, and Calvin Williams -- failed to perform CPR.

Diane's autopsy report attributed her death to "seizures due to anesthesia during an abortion," and made note of the recent pregnancy. Diane's death certificate, however, not only makes no mention of the abortion, but has the "no" box checked for whether or not the decedent had been pregnant during the previous three months.

Diane's family filed suit. A doctor reviewing the case said that Moragne and Hedd staff "deviated from the accepted standards of care [and] failed to appropriately and timely diagnose and treat intraoperative complications which resulted in her death." The clinic, Diane's family asserted, lacked the proper equipment to handle emergencies and nobody had been monitoring Diane's vital signs during the procedure.

The state Health Department had already been investigating Hedd for numerous deficiencies. Pimentel ended up paying out $1.8 million (over $6 million in 2020 dollars) in six malpractice suits, including a $500,000 (c. $1.16m)settlement to Diane's family.

Another abortion patient, Magnolia Reed Thomas, bled to death when Moragne failed to diagnose her ectopic pregnancy when she came to him at Hedd for a safe, legal abortion. Pimentel's license was suspended in 1990 for fraudulent insurance billing. He had already been banned from the state's Medicaid program for "grossly inferior care." The clinic's license was finally revoked in 1991, and Pimentel was ordered to sell it due to problems with sanitation and infection control -- including mold on the breathing tubes and mouse droppings in the procedure rooms -- and expired medications.

Watch the YouTube video.

*******

Myrtle Schall's death certificate

Florence Kruse documents:

Diane Watson documents:

On August 29, 1918, 23-year-old homemaker Mabel Johnston died at Chicago's Cook County Hospital of blood poisoning caused by an abortion involving Dr. Nathan Smedley and Dr. Emma Warren. Both were arrested and arraigned but the case evidently never went to trial.

On August 29, 1925, Katarzyna Tobiasz, age 31 or 32, died at Chicago's St. Mary's Hospital from an abortion performed on her that day. A woman whose name is spelled once as Barbara Kolur and elsewhere as Barbara Kar was held by the coroner on August 31 for Katarzyna's death. Kolur/Kar's profession is given as nurse or midwife. On July 5, 1927, she was indicted by a grand jury for felony murder in Katarzyna's death.

Self-Induced in Pittsburgh, 1926

On Wednesday, August 18, 1926, 22-year-old Myrtle Schall's friends and her fiancé, Bruce Armstrong, brought her to West Penn Hospital in Pittsburgh. She had been feverish and in pain for the past three weeks, and now she was in shock.

Bruce, who said he'd known Myrtle for six or seven years, knew only that his fiancée was terribly ill but didn't know why. Her mother, Alice Phillips, on the other hand, was able to tell the doctor more. Myrtle, she said, had attempted a self-induced abortion when her period had been two weeks later. At first her vaginal bleeding was a welcome sign that the abortion had worked, but when it continued for three weeks, accompanied by fever and pain, her family and friends had become concerned.

Myrtle had been perfectly well prior to inducing the abortion. Now she was vomiting and the doctors found her to be weak and anemic, with a rapid pulse and respiration and an alarming blood pressure of 136/100. In spite of all of the doctors' best efforts, Myrtle died from peritonitis at 8:15 p.m. on Sunday, August 29.

Myrtle's death certificate indicates that she was married to John Schall at the time of her death. Since Bruce was listened as the source of the information, and Myrtle was buried under her maiden name, it's likely that she and her husband were estranged and that she was awaiting a divorce so that she and Bruce could marry.

Abused and Abandoned in Chicago, 1927

In August of 1927, fifteen-year-old Florence Kruse, a junior at Lindblom High School, confessed to her parents that she was pregnant. Corwyn Lynch, an insurance adjuster in his early 20s, promised to marry Florence, then disappeared on August 15, telling his landlady that he was going to California. The deserted teen was disconsolate and began talking about suicide. That's when her parents, Louis and Amanda, reached out to Dr. James Aldrich, age 71.

On August 19, Mr. and Mrs. Kruse took Florence Aldrich's office at 5941 Normal Boulevard. After the abortion, Florence remained at Aldrich's office, attended by his wife. Her condition deteriorated over the ensuing week, and she was taken to Augustana Hospital. The doctors who treated her there reported the case to the coroner's office. A deputy spoke to Mr. Kruse, who admitted what they'd done.

Florence died on August 29. Deputy Coroner Joseph Kveton conducted an inquest at the Reilly undertaking establishment. After the funeral he had the girl's parents, Florence's parents, charged as accessories before and after the fact.

Mrs. Kruse wasn't home when police went to arrest her but was reportedly ill at another location. Mr. Kruse, evidently unable to raise the $5,000 bond, sat in a jail cell and threatened to kill Lynch.

The three parties in Chicago were released after the coroner's jury was unable to confirm that Aldrich had performed the abortion. The coroner recommended that Lynch be charged with murder.

I've been unable to learn anything more about the case.

Filthy and Substandard in Chicago, 1987

Diane Watson was 27 years old, a mother of two, when she went to Hedd Surgi-Center in Chicago for a safe and legal abortion on August 29, 1987. Although Diane was over 12 weeks pregnant, Rudolph Moragne proceeded with the abortion, in violation of state regulations prohibiting outpatient abortions after 12 weeks. He ended up hitting a vein when injecting anesthetics. Diane had seizures and went into cardiac arrest. Moragne and the other physicians present -- Henry Pimentel, Ester Pimentel, and Calvin Williams -- failed to perform CPR.

Diane's autopsy report attributed her death to "seizures due to anesthesia during an abortion," and made note of the recent pregnancy. Diane's death certificate, however, not only makes no mention of the abortion, but has the "no" box checked for whether or not the decedent had been pregnant during the previous three months.

Diane's family filed suit. A doctor reviewing the case said that Moragne and Hedd staff "deviated from the accepted standards of care [and] failed to appropriately and timely diagnose and treat intraoperative complications which resulted in her death." The clinic, Diane's family asserted, lacked the proper equipment to handle emergencies and nobody had been monitoring Diane's vital signs during the procedure.

The state Health Department had already been investigating Hedd for numerous deficiencies. Pimentel ended up paying out $1.8 million (over $6 million in 2020 dollars) in six malpractice suits, including a $500,000 (c. $1.16m)settlement to Diane's family.

Another abortion patient, Magnolia Reed Thomas, bled to death when Moragne failed to diagnose her ectopic pregnancy when she came to him at Hedd for a safe, legal abortion. Pimentel's license was suspended in 1990 for fraudulent insurance billing. He had already been banned from the state's Medicaid program for "grossly inferior care." The clinic's license was finally revoked in 1991, and Pimentel was ordered to sell it due to problems with sanitation and infection control -- including mold on the breathing tubes and mouse droppings in the procedure rooms -- and expired medications.

Watch the YouTube video.

*******

Myrtle Schall's death certificate

Florence Kruse documents:

- "Girl's Parents Held as She Dies After Illegal Operation," Des Moines Tribune, August 30, 1927

- "Arrest Doctor After Operation Kills H.S. Girl," Chicago Tribune, August 29, 1927

- "Girl's Parents Ordered Held in Death Quiz," Chicago Daily Tribune, August 30, 1927

Diane Watson documents:

- "Health care system is failing to weed out dangerous doctors," Chicago Tribune, June 11, 1990

- "Discipline sought for physician," Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1990

- "Medical clinic has license revoked," Chicago Tribune, February 8, 1991

Friday, August 28, 2020

August 28: Mom of Ten Dies in Chicago and Could an Infected Toenail Really Kill?

Ten Children Left Motherless

On August 28, 1926, 44-year-old Margaret Muscia, an Italian immigrant and mother of 10, died from a criminal abortion performed that day in Chicago. Mrs. Minnie Miller, alias Molinaro, was arrested on July 10 for Margaret's death. Minnie's profession is not given. On November 15, she was indicted for felony murder by a grand jury.

Blame it on the Ingrown Toenail

Naomi Congdon, age 21, was the wife of Donald Congdon, a sailor from Denver, stationed in Norman, Oklahoma. On July 27, 1943, Dr. Andrew Young examined Naomi and noted that she was pregnant, and also that she had an ingrown toenail that was infected. The infection, he said, was "minor".

Naomi told her husband that she wanted to "do something" about the pregnancy. She even admitted to him that she had ingested turpentine to try to cause an abortion, but had vomited it back up. Donald objected to the idea of an abortion.

On August 16, Donald found a note from his wife, telling him that she was at the home of Mrs. Lena Griffin Smith, a 63-year-old maternity nurse in Oklahoma City. Donald went there and found his wife in great pain. He called a medical officer at the base, who went with him to the house and found Naomi so sick that he told Donald to have Naomi brought to the base hospital. Donald called an ambulance and rode with his wife.

Police raided Smith's practice at her residence at 2134 Harden Drive. News said that Smith was caught "literally red-handed," bloody from an abortion she had just completed on a 23-year-old Oklahoma City woman who was recuperating in bed. The police made Smith return the woman's abortion fee of $200 (just over $3,000 in 2020 dollars). They took the woman to a hospital. Later that night she gave birth to an infant that lived little more than an hour. Smith was charged with first degree manslaughter for the baby's death.

Smith confessed that she had been operating an abortion business for about 15 years in a house described as "luxurious." She had an accomplice, Mrs. Pearl Green, who was also a nurse. Smith herself had attended medical school for two years.

On August 19, a Navy doctor examined Naomi and found she had a fever of 103 from an infection that appeared to have started in her uterus. He administered sulfa drugs and blood transfusions. Despite the efforts of the Navy doctors, Naomi died of septicemia on August 28. Her body was taken home to Colorado for burial.

Smith's defense claimed that Naomi had already been feverish when she'd come for care, and that the fatal infection had originated in the ingrown toenail. The jury found Smith guilty of manslaughter and recommended a 10-year sentence. She was also charged with attempting to conceal the death of a child under the age of two after police found the body of an infant who had been born alive during an abortion attempt on its 17-year-old mother at Smith's home before perishing.

Watch the video on YouTube.

Additional sources:

On August 28, 1926, 44-year-old Margaret Muscia, an Italian immigrant and mother of 10, died from a criminal abortion performed that day in Chicago. Mrs. Minnie Miller, alias Molinaro, was arrested on July 10 for Margaret's death. Minnie's profession is not given. On November 15, she was indicted for felony murder by a grand jury.

Blame it on the Ingrown Toenail

Naomi Congdon, age 21, was the wife of Donald Congdon, a sailor from Denver, stationed in Norman, Oklahoma. On July 27, 1943, Dr. Andrew Young examined Naomi and noted that she was pregnant, and also that she had an ingrown toenail that was infected. The infection, he said, was "minor".

Naomi told her husband that she wanted to "do something" about the pregnancy. She even admitted to him that she had ingested turpentine to try to cause an abortion, but had vomited it back up. Donald objected to the idea of an abortion.

On August 16, Donald found a note from his wife, telling him that she was at the home of Mrs. Lena Griffin Smith, a 63-year-old maternity nurse in Oklahoma City. Donald went there and found his wife in great pain. He called a medical officer at the base, who went with him to the house and found Naomi so sick that he told Donald to have Naomi brought to the base hospital. Donald called an ambulance and rode with his wife.

Police raided Smith's practice at her residence at 2134 Harden Drive. News said that Smith was caught "literally red-handed," bloody from an abortion she had just completed on a 23-year-old Oklahoma City woman who was recuperating in bed. The police made Smith return the woman's abortion fee of $200 (just over $3,000 in 2020 dollars). They took the woman to a hospital. Later that night she gave birth to an infant that lived little more than an hour. Smith was charged with first degree manslaughter for the baby's death.

Smith confessed that she had been operating an abortion business for about 15 years in a house described as "luxurious." She had an accomplice, Mrs. Pearl Green, who was also a nurse. Smith herself had attended medical school for two years.

On August 19, a Navy doctor examined Naomi and found she had a fever of 103 from an infection that appeared to have started in her uterus. He administered sulfa drugs and blood transfusions. Despite the efforts of the Navy doctors, Naomi died of septicemia on August 28. Her body was taken home to Colorado for burial.

Smith's defense claimed that Naomi had already been feverish when she'd come for care, and that the fatal infection had originated in the ingrown toenail. The jury found Smith guilty of manslaughter and recommended a 10-year sentence. She was also charged with attempting to conceal the death of a child under the age of two after police found the body of an infant who had been born alive during an abortion attempt on its 17-year-old mother at Smith's home before perishing.

Watch the video on YouTube.

Additional sources:

- "'Motherly' Type is Held as Chief of Abortion Mill," Daily News, October 10, 1943

- "Appeal Is Lost By Abortionist," Daily Oklahoman, December 5, 1946

Thursday, August 27, 2020

August 27: Scant Info on Two Tragedies

Victoria Seronka, a 17-year-old homemaker, died on August 27, 1970 in transit by ambulance to Southwest General Hospital in Cleveland, Ohio. Doctors said that she was 3 months pregnant, and an autopsy revealed signs of an attempted abortion.

Watch the video on YouTube.

Tuesday, August 25, 2020

August 25: The Unwilling Widower and his Teenage Housekeeper

In April of 1893, 17-year-old Ada Hawk was living with her parents, Eliza J. and Samuel M. Hawk in Walnut Grove, Missouri. John O. Edmonson, a bank vice-president and middle-aged widower, hired her to serve as a live-in housekeeper for the home he shared with his mother in Greene County, about a mile from her family.

When summer came, Edmonson began trying to cajole several men into marrying Ada so that her impending baby would have a legitimate father. This was a plan she reportedly resented. Unwilling to marry Ada himself and unable to recruit another husband for her, Edmonson began asking around for the best way to "get rid of it." Ada seemed willing to go along with this plan. She and Edmonson first tried inserting a rubber catheter, to no effect. Edmonson consulted with a druggist who said he didn't know how to cause an abortion. Edmonson asked if whiskey and "Indian turnip," more commonly known as Jack-in-the-pulpit, would do the job. King indicated that there was a place near Walnut Grove where Indian turnip could be found.

Having had no success with the catheter -- or, if they tried it, "Indian turnip" -- Edmonson took Ada to Springfield on July 10, where a doctor had supposedly agreed to perform an abortion for $50 (over $1,400 in 2020 dollars). Ada then checked in to the Commercial boarding house in Springfield with Edmonson on August 28. The elderly Mrs. Donaldson, who was keeping the boarding house, insisted that while Ada had told her of the pregnancy and requested help getting rid of it, she'd refused to do anything to abort the pregnancy. Evidently, at some point in the journey, some sort of concoction was also given to Ada.

Ada's mother reported that Ada had come home on August 1 and had taken sick on the 5th, reporting pain in the stomach and bowels. Edmonson coached Ada on how to hide the abortion from her mother and was very attentive of her during her illness. Some two or three weeks passed during which Ada kept her secret and continued to take some greenish medicine Edmonson had provided. The medicine seemed to make Ada more ill. She bled heavily and passed a clot, which led her mother to wonder if her daughter had been pregnant and had aborted.

Both Ada's parents said that they insisted on sending for a doctor, wanting Dr. Hardin, the family physician. Ada, however would only consent to the doctor Edmonson chose, Dr. Perry.

"That excited my suspicions that my daughter had not done right," Mr. Hawk testified. "I asked her about it but she made no reply. She never made any confidential statement to me after or during her sickness."

Dr. J. K. Perry testified that Edmonson had come to his office on August 21, asking him to tend to Ada for her headache and bowel pain. Perry arrived to find her with a fever of 103, and was told that she'd been delirious. He diagnosed her as having typhoid malarial fever and denied that she was pregnant when he treated her.

Perry came nine times to care for Ada, Mr. Hawk said, and always insisted that everybody leave the room while he attended to her.

Perry came nine times to care for Ada, Mr. Hawk said, and always insisted that everybody leave the room while he attended to her.

As her health deteriorated, Ada realized that she was dying and said to her mother, "Ma, how I love you. You will keep our secret, won't you?"

Mrs. Hawk promised that she would.

"Well, Ma, I did miscarry the Saturday after I came home [August 5]." Ada had gone into the woods to deliver the baby, then returned to the house and acted as if nothing had happened.

Mrs. Hawk promised that she would.

"Well, Ma, I did miscarry the Saturday after I came home [August 5]." Ada had gone into the woods to deliver the baby, then returned to the house and acted as if nothing had happened.

The dying girl turned to Edmonson and said, "John, you know that it was yours, for you forced me, and you know you forced me. You know you did and you can be punished for it yet. Are you going to do what you said you would? You said you would take care of me, and if you don't I will commit suicide."

Edmonson told Ada to be quiet and stop making herself so upset.

Edmonson told Ada to be quiet and stop making herself so upset.

Ada died on August 25. Mrs. Hawk further testified that after her daughter died, "Mr. Edmonson told me that if I would get my husband quiet he would do what was right by us. "

Ada's father testified that, "Mr. Edmonson did not ask me to keep my mouth shut in regard to my daughter's death, but he said he would pay for the hauling of the coffin and of the corpse. He said he would not go to my house so much only to keep suspicion down."

After Ada's death, Edmonson asked a Mr. Brown to help him dig a grave, telling Brown that "he wanted her buried quick" and that "the family wanted a shallow grave." Word got to the authorities about the suspicious circumstances. Edmonson was arrested then released on $500 bond (over $14,000 in 2020 dollars). The coroner arrived in town and had Ada's body exhumed, but it was too decomposed for him to be able to perform a satisfactory autopsy. Instead he held the inquest that brought the story out.

Edmonson, for his part, had conveniently hopped into a buggy and stayed out of town for the entire time the coroner was there investigating Ada's death. This did little to help him, as the coroner swore out a new warrant and bond was set at $2,000 (over $57,000 in 2020 dollars).

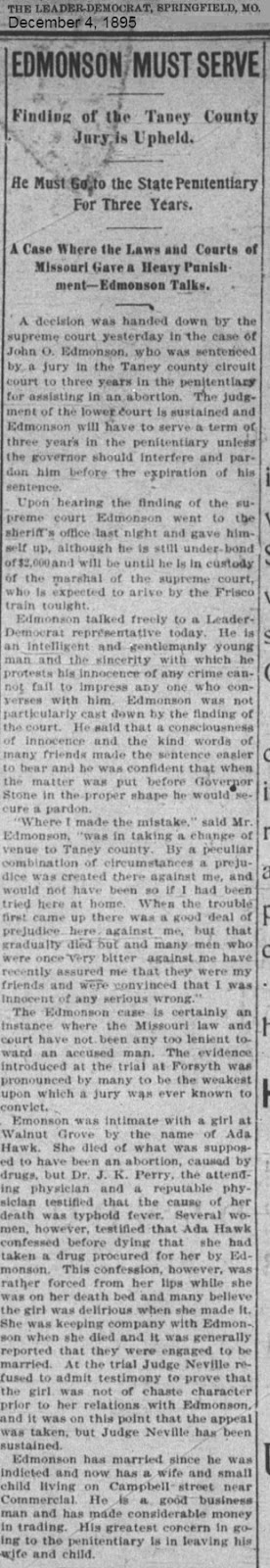

When the time came for his trial, Edmonson managed to get a change of venue from Greene County to Taney County, which did nothing to help him. Edmonson was convicted of manslaughter in the second degree. Though he appealed his case the conviction was upheld.

Ada's father testified that, "Mr. Edmonson did not ask me to keep my mouth shut in regard to my daughter's death, but he said he would pay for the hauling of the coffin and of the corpse. He said he would not go to my house so much only to keep suspicion down."

After Ada's death, Edmonson asked a Mr. Brown to help him dig a grave, telling Brown that "he wanted her buried quick" and that "the family wanted a shallow grave." Word got to the authorities about the suspicious circumstances. Edmonson was arrested then released on $500 bond (over $14,000 in 2020 dollars). The coroner arrived in town and had Ada's body exhumed, but it was too decomposed for him to be able to perform a satisfactory autopsy. Instead he held the inquest that brought the story out.

Edmonson, for his part, had conveniently hopped into a buggy and stayed out of town for the entire time the coroner was there investigating Ada's death. This did little to help him, as the coroner swore out a new warrant and bond was set at $2,000 (over $57,000 in 2020 dollars).

When the time came for his trial, Edmonson managed to get a change of venue from Greene County to Taney County, which did nothing to help him. Edmonson was convicted of manslaughter in the second degree. Though he appealed his case the conviction was upheld.

Edmonson, who had relocated to Springfield, married and become a father since Ada's death, was sentenced to three years in the state penitentiary. In an interview he told a reporter that he was innocent and appreciated the support he was getting from his many friends. He planned to petition the governor for clemency.

Sources:

- "Abortion Suspected," St. Louis Post Dispatch, August 28, 1893

- "It Was Abortion," Springfield Leader and Press, August 29, 1893

- "Her Dark Secret," Springfield Democrat, August 29, 1893

- "Trial Tomorrow," Springfield Leader and Press, September 1, 1893

- "Edmonson Must Serve," Springfield Leader Democrat, December 4, 1895

- Parents' names found in census records

August 26: The Trunk Mystery and Two Other Tragedies

On August 26, 1871, a shabbily-dressed young woman waited on the platform of the Hudson River Railroad Depot in New York City. A trunk was delivered to her by a hired driver. The young woman checked the trunk for Chicago -- her own destination -- then vanished in the crowd. As the flimsy trunk was hauled to the platform, the lid was jarred, and an overpowering stench filled the balmy summer air. The station master opened the trunk to find bloodstained quilts and rags -- and the nude body of a young woman. She was eventually identified by her dentist as 25-year-old Alice Bowlsby of Patterson, New Jersey. On August 31, the day Alice's name was first published in the newspaper, the baby's father, a wealthy young man named Walter Conklin, committed suicide by shooting himself. An investigation eventually led police to her abortionist, Dr. Jacob Rosenzweig, who in a sensational trial was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to seven years of hard labor at Sing-Sing.

On August 26, 1917, 28-year-old Mrs. Valdislaw Zapanc (I have been unable to determine her first name) died at Chicago's Englewood Hospital from a criminal abortion performed by some unknown perpetrator.

On August 26, 1922, Catherine Wainwright, whose husband was working in South America as a civil engineer at the time, died at Nassau Hospital, Long Island, New York. She was taken there after having been treated at her home since August 21 for what was diagnosed as "a gastro-intestinal infection." "There was plain evidence that the woman had undergone an illegal operation shortly before her death from mercury poisoning," news reports said. The autopsy revealed that she had been about three months into her pregnancy.

On August 26, 1917, 28-year-old Mrs. Valdislaw Zapanc (I have been unable to determine her first name) died at Chicago's Englewood Hospital from a criminal abortion performed by some unknown perpetrator.

On August 26, 1922, Catherine Wainwright, whose husband was working in South America as a civil engineer at the time, died at Nassau Hospital, Long Island, New York. She was taken there after having been treated at her home since August 21 for what was diagnosed as "a gastro-intestinal infection." "There was plain evidence that the woman had undergone an illegal operation shortly before her death from mercury poisoning," news reports said. The autopsy revealed that she had been about three months into her pregnancy.

Monday, August 24, 2020

New for August 24: One of Dr. Charles Earll's Victims

"It was 2 o'clock on the morning of Aug. 27 that she died, having all the previous day and that night been submitting to his infamous practice. Finding her dead on his lounge, he had carried her out in his arms to the hall, placed a bottle of chloroform in her lifeless hand, and left her there in the glow of the gaslight to drive people into the belief that she had committed suicide and had not been murdered by him." -- "Etta Carl," The Daily Inter Ocean, December 4, 1880

Policeman J. B. Davis lived at 205 West Madison Street in Chicago, in the same building as Dr. Charles Earll. He gave the following statement: "I have known Dr. Earll for about a year and a half. .... At about 2 o'clock this (Tuesday) morning [August 25, 1880] I was on duty, and went to my room to change my shoes. When I went upstairs I saw nothing in the hall, though the gas was lighted. After returning to the sidewalk I stood near the entrance talking to officer [James] Derig [or Derring]. We heard a noise at the head of the stairs, like the rustling of a dress, and went up to see what was the matter. When we got nearly to the top I saw Dr. Earll in his shirt-sleeves, with a cloth in his hand wiping up something in front of his door. He sprang at once into his room and locked the door. We looked around the hall, and found the body of a woman, near a gas-jet, about thirty feet from the stairs, and almost in front of a room occupied by Dr. Smith. I examined the remains sufficiently to ascertain that she was dead, and then I went to Dr. Earll's door and rapped. After some delay he asked if I was Policeman Davis. I replied that I was, and after a few moments he opened the door. He then had his coat on, and Officer Derig and I took charge of him and his son, who was also in the room. Coming out, we walked within ten feet of the corpse, and the Doctor threw up his hands and exclaimed, 'My God, what is this?'"

Coroner Mann was at once notified of the case, and reached the building at 3 o'clock in the morning. After taking a survey of the surroundings, and finding in the right hand of the deceased a two-ounce phial containing some chloroform, he ordered the body to be taken into Dr. Earll's office, which was locked up and a policeman stationed at the door. At 9 o'clock the County Physician arrived and proceeded to make a post-mortem examination, and then suspicion became a fact, -- the woman's death was caused by an abortion. -- Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1880

Who she was no one could tell. Her age was about 20, and her face not ill-looking. She wore very good clothes, and on her fingers were three rings, -- a heavy gold one, and amethyst setting, and an octagonal with the initials 'E.A.C.' While speculations as to her identity were being indulged in, a tall woman of 40, in black, who had gotten off a street-car, forced her way through the crowd around the entrance to the building, and, being shown the hat of the dead girl, cried out that it was her child's. She asked to see the body, immediately identified it, and was overcome by grief. Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1880

The deceased was 19 years of age, and her name was Etta A. Carll. She had been born in Wisconsin, and her father, who belonged to Company D, Thirty-sixth Wisconsin, was killed at Petersburg. Her mother married again, and is now Mrs. Susan C. Cure, but a widow, her second husband also being dead. She and her daughter came to Chicago from Oconomowe in February, and roomed at No. 683 West Lake street. They had earned a living by making overalls for the Lakeside Manufacturing Company. Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1880

A Coroner's Jury was assembled in Earll's premises. The first witness was Officer Davis. Earll then testified, "I have no regular license for practicing medicine, and never have had any. [A license was not required to practice medicine in Chicago at that time.] I am not a graduate, but attended lectures at Lynn University, now known as the Chicago Medical College. I saw the body found in the hall of the building where I reside. I placed it there. I have seen the person alive. I saw her four of five times since my first acquaintance, which began fore or five weeks ago. She thought herself pregnant; I examined her, and told her I thought she was. I did not do anything to her at that time, although she urged me to produce an abortion upon her. I declined to do so. Several days afterwards she came to me again, and repeated her request. Then I made a demonstration, using no instrument, in order to giver her the impression that I had performed an operation. She went away, and several days later returned and said no effect had been produced. I repeated the same demonstration four of rive times at intervals of four, or five, or eight, or ten days. I never used an instrument; but my impression is that I used a sponge-tent. That was at the next to the last visit, which was four or five days previous to Monday. There as no hemorrhage so far as I know. I don't think she had any fever. She never paid me one cent. She claimed to be a poor girl, without the means of support except such as she obtained by helping some woman at sewing. She never gave me any jewelry or valuables. I treated her out of charity. She called on me between 3 and 4 o'clock Monday afternoon, and I at her request injected some water. She immediately complained of pain in her heart, and of feeling faint. I administered about ten grains of carbonate of ammonia and two tablespoonfuls of whisky. She swallowed at first, but toward the last it ran out of of her mouth. Death followed about five minutes after I ceased giving her the medicine. I should judge it was a little after 4 o'clock when she died -- about half an hour after the injection. She did not complain of pain in the abdomen. I did not know what to do after she died. Her death threw me into a state of excitement so that I scarcely knew what to do. I first thought of reporting the case to the police; but it went on until late at night, when, under a high state of excitement, I took the body up and carried it into the hall, putting it down in about the centre, almost directly under the gaslight. In carrying the body out I opened the door of my office. That created a draft, and the gas in the hall went out. I lighted it again. As soon as I did so I stepped inside my door, locked it, and went to bed. I had been there but a short time when the officers came and arrested me. My son returned about half-past 9 o'clock, and was in bed all the time. He did not see the lady until we went into the hall." He said that nobody had helped him attend to Etta. "I did not put the bottle in her hand, but noticed it when under the gaslight in the hall."

Earll's 14-year-old son, Charles Frederick Earll, said that he'd eaten supper at his aunt's home and returned at around 10:30 p.m. He was awakened by the sound of his father asking, "Is your name Davis?" He said he saw the body in the hall but didn't hear his father make any exclamation about it. He, Charles Jr., said he didn't recall ever having seen the woman before.

Earl was shown a watch case and a small watch which had been found in the bureau of his office. He admitted that Etta had left it with him two or three weeks ago, "as she supposed, for the purpose of securing me for my services." When asked why he accepted the watch if he was treating Etta out of charity, he replied that the watch was precious to Etta and she wanted to get it repaired "and urged me to take possession of it and keep it for the present."

Etta's body was brought into Earll's office and placed on a table for the post-mortem examination. Etta was plump, weighing around 140 pounds. In her right hand was a bottle containing 3 or 4 drams of chloroform. Bloody froth was oozing from her nose. Her internal organs were normal and healthy except for inflamed reproductive organs. Bluthardt couldn't seem to make up his mind what had caused Etta's death. He said at an injection of water, which Earll said he'd administered, would constitute "no practice," not malpractice. But he also postulated that the injection might have caused sudden death from an embolism. But then, an embolism might have been caused by a disease of the blood vessels which would then throw off a clot. Bluthardt first sent a written opinion to the coroner giving peritonitis as the cause of death, but under questioning said that he should have added "and shock" either before of after "peritonitis." Her brains, lungs, and liver looked healthy but her stomach was irritated and her intestines and peritoneum were inflamed. He believed that her death was due to acute peri-metritis caused by an abortion attenpt. Etta was, he said, about three months into her pregnancy at the time of her death.

18-year-old, two months shy of turning 19

Earll's attorney, Gus Van Buren, admitted in court that his client had indeed performed a procedure on Etta Carl. As the Daily Inter Ocean reported, Van Buren "spoke of his client, Earll, as one who had intended to do the young woman a service and not an injury. It was a benevolent act, he said, that a doctor did when he sought to relieve a woman of shame and the possibility of dishonor and not a manevolent one. In this case the girl had come to him and begged to be relieved of her child. Earll had operated upon her, but his manipulations were harmless, and done with the attempt of leading her to believe that he was ridding her of the child, when in fact he was not doing so. Death came while she was in Earll's office. It was like a thunder-clap to him, startling in the extreme. He knew not what to do, and in a moment of thoughtlessness carried her into the hallway, where the police officer found him."

Earll testified at the Coroner's Inquest that Etta had come to him five or six weeks prior to hear death asking him to perform an abortion. He had refused, but she kept coming back to his office and asking for an abortion so he decided to perform a fake abortion in order to placate her.

Earll admitted that a watch found in his possession was Etta's and that she had given it to him. The instruments found in Earll's office were normal obstetrical instruments.

Van Buren asserted that the county physician who had performed the autopsy had originally not attributed Etta's death to abortion but had changed his ruling because he was coming near the end of his term and, to secure a re-election, "he has hatched this case and all the evidence against the prisoner."

Etta's mother, Susan Cure, attended the trial dressed in deep mourning, not even removing her thick veil while testifying. Etta was the child of her first marriage to a soldier who had been killed in the war. Her voice was so low that the court stenographer had to repeat her answers. She and Etta had lived in Milwaukee and had moved to Chicago the preceding February. Etta had been in good health on Tuesday, August 24. Etta and Susan had ridden on a streetcar downtown on the 24th and gotten off the cars near Clark Street to do some shopping, eat lunch in a restaurant, and walk around the city. They got on the Randolph Street streetcar and headed home. Etta had gotten off at the corner of Green and Randolph at around 3:00. The next time she saw her was at the coroner's inquest in Earll's office. She hadn't known about the pregnancy. Susan gave conflicting testimony about whether she had been to Earll's office with Etta or if the first time she'd been there was at the inquest. "I never heard of Dr. Earll or anything about him until my daughter said somebody advised her to go and see him. That was three or four weeks ago. She said she didn't know whether anything was the matter with her or not. He told her to come again in a few days. She went two or three days afterwards. He said he wouldn't do anything for her unless she paid him $25 - 85 down. She told him she didn't have any money, and didn't know where she could raise any, but would see what she could do. She had a little gold watch, and she said she would go and see if she couldn't pawn it and raise money. She went to his office, and he asked her what she had in the box. She told him. He asked what she was going to do with it. she said, 'pawn it and get money.' He asked if she had any objections to leaving it with him. She said 'No,' and he took it. I understood that the watch was left as security. If she got the money she was to redeem it. She went to see him several times. I tried all I could not to have her go. I had no idea that she was enceinte. I told her it could not be possible, because there were no symptoms indicating it. I cannot tell who was likely to be the father of the child. My daughter went to Milwaukee in the spring, -- about the 1st of May. She was there three weeks. It must have been then. I don't know how often she visited Dr. Earll. I don't know who recommended her to go to him. She did not tell me the lady's name. One evening I went with her to his office. He was there, and she introduced me, but I had no conversation with him. She visited him last week, but did not tell me what treatment he resorted to. She said he made an examination. I never asked about instruments. Tuesday we were downtown, and started home on a Randolph street car. She got off at Green street, saying she was going over to Madison, -- that she would not be gone but a few minutes. She didn't say she was going to see Dr. Earll, but that was my idea. That was about 3 o'clock. She didn't come home during the night, and I thought she had gone to her brother's. I felt somewhat uneasy, and I started down-town to find her. I thought I would step into Dr. Earll's office and inquire. When the car came near his number I noticed the crowd, and I then learned of her death, and identified the body. My daughter was in good health, and had no indications of heart disease."

Earl was arrested six times from 1874 to 1880, though there were 18 months between his most recent arrest and Etta's death. "[W]hile there was no doubt as to his guilt in nearly every instance, the legal proof in all the cases except one was insufficient, and in that the jury were somehow induced to fix his punishment at only one year in the Penitentiary." Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1880

Earll was first arrested in the spring of 1874 for perpetrating an abortion on a woman named Talfrey. He was released. A month or two later he was arrested for the death of Rosetta Jackson. He was convicted and sent to Joliet and served 11 months -- his one-year sentence and a month off for good behavior. He was released in August of 1875. A young woman named Creighton died in October of 1876, and Earll was not held legally accountable. In August of 1877 he was investigated for the death of a young woman named Morgan. The next year he was arrested for performing an abortion on Mrs. McKay, held over for a trial by the Coroner's Jury, but not indicted by the Grand Jury.

Earll's practice was in Room 10 at 207 West Madison Street. His place was divided into a consulting room, a "medicine room," two bedrooms, and another small room. "All are dirty and dingy, full of rubbish of all sorts, and the atmosphere is sickening." Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1880

Coroner's Jury verdict: "That the said Etta A. Carll came to her death on the 24th of August, at the office of Dr. Charles Earll, Room 10, No. 205 West Madison street, by reason of acute peri-metritis, caused by an attempt to produce an abortion; the the jury further find that the said attempt to produce an abortion was made by Dr. Charles Earll, and we therefore recommend that the said Charles Earll be held to await the action of the Grand Jury.

One weakness in the case against Earll was that there were no signs of instrumentation. The doctor believed that the water Earll "injected" caused "uterine colic." "Abortion is a very difficult crime to prove, and, while there is no chance for hanging 'Dr.' Earll this time, it will be well to send him to Joliet for at least twenty years. That would certainly end his career, for he is over 50 now, and would never come out alive." The Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1880

Dr. J. W. Hutchinson testified in the trial that Etta had died from a shock caused by the injection of cold water. He said that sometimes doctors will perform a water injection but he himself considered it dangerous, especially during pregnancy.

During the trial Officer Davis testified that he'd seen bloody froth on a pillow in Earll's office consistent with what had been exuding from Etta's mouth and nose. He also said that Earll told him that he thought Etta had died of heart disease, the prior to her death her lips turned white and her face turned living, and she put her hand over her heart and complained of pain there. Bluthardt testified that he thought the abortion had been attempted first by manipulation, then by sponge-tents, then by the cold water injection. Earll's attorney objected to this conjecture.

Sources:

- "Dr. Charles Earll," The Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1880

- "The Courts," The Chicago Tribune, September 8, 1880

- "Etta Carl," The Daily Inter Ocean, December 4, 1880

- "The Earll Abortion Case," The Inter Ocean, December 6, 1880

- "Trial of Dr. Earll," Chicago Tribune, December 7, 1880

August 24: Short Shrift to a Possible Hagenow Victim, and the Mystery Death of an Heiress

The End of Hagenow's San Francisco Reign

On August 24, 1888, Mrs. Emma Dep, who had recently been discharged from a maternity home run by known abortionist Dr. Louisa Hagenow, died at 537 Second Street in San Francisco. The San Francisco Bulletin indicated that a Dr. Erenberg signed the death certificate attributing the death to peritonitis from a self-induced abortion.

I find it a bit odd that there was no evidence of a real investigation of the death. There is simply no explanation that makes any sense other than that Emma had gone to known Hagenow, had an abortion at the maternity home, thought she was recovering, went home, and died. Considering that there had recently been three Hagenow patients dying from botched abortions -- Louise Derchow, Anna Doreis and Abbia Richards -- one would think that they'd dig deeper into the circumstances surrounding Emma's death. Furthermore, a man named Franz Krone had died on August 13 at Hagenow's maternity home, leaving behind jewelry and money that was never accounted for.

Hagenow promptly relocated to Chicago, began using the name Lucy rather than Louise or Louisa, and began piling up dead bodies there as well. She was implicated in numerous abortion deaths, including Minnie Deering, Sophia Kuhn , Emily Anderson, Hannah Carlson, Marie Hecht, May Putnam, Lola Madison, Annie Horvatich. Lottie Lowy, Nina H. Pierce, Jean Cohen, Bridget Masterson, Elizabeth Welter, and Mary Moorehead.

On August 24, 1888, Mrs. Emma Dep, who had recently been discharged from a maternity home run by known abortionist Dr. Louisa Hagenow, died at 537 Second Street in San Francisco. The San Francisco Bulletin indicated that a Dr. Erenberg signed the death certificate attributing the death to peritonitis from a self-induced abortion.

I find it a bit odd that there was no evidence of a real investigation of the death. There is simply no explanation that makes any sense other than that Emma had gone to known Hagenow, had an abortion at the maternity home, thought she was recovering, went home, and died. Considering that there had recently been three Hagenow patients dying from botched abortions -- Louise Derchow, Anna Doreis and Abbia Richards -- one would think that they'd dig deeper into the circumstances surrounding Emma's death. Furthermore, a man named Franz Krone had died on August 13 at Hagenow's maternity home, leaving behind jewelry and money that was never accounted for.

Hagenow promptly relocated to Chicago, began using the name Lucy rather than Louise or Louisa, and began piling up dead bodies there as well. She was implicated in numerous abortion deaths, including Minnie Deering, Sophia Kuhn , Emily Anderson, Hannah Carlson, Marie Hecht, May Putnam, Lola Madison, Annie Horvatich. Lottie Lowy, Nina H. Pierce, Jean Cohen, Bridget Masterson, Elizabeth Welter, and Mary Moorehead.

Rich and Dead in Philadelphia

On

August 25, 1955, the body of a young woman identified as Shirley

Silver lay in the morgue in Philadelphia, where it had been since

being brought there the previous day from the North Philadelphia

apartment of bartender Milton Schwarts and his beautician wife,

Rosalie. The young woman, they said, had suddenly taken ill and

collapsed while sitting on a sofa in their living room. But when

machinations began to try to remove the young woman's body without an

autopsy, her real identity was revealed, and a scandal rocked the

city.

The dead woman was Doris Jean Silver Ostreicher, a 22-year-old heiress. Doris had made front page news when she eloped in a "fairy tale romance" with Earl Ostreicher, a 29-year-old motorcycle cop from Miami Beach, in late June of 1955. Ostreicher was the son of a Chicago fuel dealer. He held that he'd not known that his beautiful red-haired bride was wealthy. She'd told him, he said, that her father was a butcher, not vice president of the Food Fair chain of grocery stores.

But fairy tale romances don't always lead to fairy tale marriages. Within a few weeks, Doris evidently was disillusioned, and had separated from her husband, returning to her family's Philadelphia home. When she learned that her short-lived marriage had left her pregnant, her mother, Gertrude Silver, helped her to arrange an abortion, which was perpetrated with some sort of instrument and a "vegetable compound." Doris collapsed and died.

The dead woman was Doris Jean Silver Ostreicher, a 22-year-old heiress. Doris had made front page news when she eloped in a "fairy tale romance" with Earl Ostreicher, a 29-year-old motorcycle cop from Miami Beach, in late June of 1955. Ostreicher was the son of a Chicago fuel dealer. He held that he'd not known that his beautiful red-haired bride was wealthy. She'd told him, he said, that her father was a butcher, not vice president of the Food Fair chain of grocery stores.

But fairy tale romances don't always lead to fairy tale marriages. Within a few weeks, Doris evidently was disillusioned, and had separated from her husband, returning to her family's Philadelphia home. When she learned that her short-lived marriage had left her pregnant, her mother, Gertrude Silver, helped her to arrange an abortion, which was perpetrated with some sort of instrument and a "vegetable compound." Doris collapsed and died.

When

police searched the Schwartz apartment, they found abortion

instruments there, including syringes, medications, dry mustard,

absorbent cotton, mineral oil, and olive oil, along with a metal tube

that was believed to be the fatal instrument in Doris' abortion. The

Schwartzes pleaded no contest for their role in the young woman's

death. Rosalie got a sentence of indeterminate length, while Milton

was sentenced to 3-10 years. Both were paroled after 11 months, based

on a "pathetic" letter from their gown son asking that his

parents be freed in time for Christmas.

Doris' mother, who was hospitalized for "bereavement shock" in the early days after her daughter's death, was charged as an accessory. She was fined and given a suspended sentence for her role in her daughter's death. The judge said that he considered the memory of how her daughter had died "substantial punishment."

Doris' mother, who was hospitalized for "bereavement shock" in the early days after her daughter's death, was charged as an accessory. She was fined and given a suspended sentence for her role in her daughter's death. The judge said that he considered the memory of how her daughter had died "substantial punishment."

Sunday, August 23, 2020

1940: The Abortion Death that Wasn't

On November, 13, I blogged about the lack of information verifying the purported illegal abortion death of Pauline Roberson Shirley. Pauline's is one of a cluster of stories abortion-rights activists use to exemplify illegal abortion deaths.

I'd always known there was a significant problem with their claim about Becky Bell -- there is absolutely zero evidence that Becky underwent an abortion. Every piece of evidence in her death indicates that she had a miscarriage while dying of the same strain of pneumonia that killed Muppets creator Jim Henson.

Up until recently, I'd been unable to find a scintilla of information about Pauline Roberson Shirley outside of verbatim repetitions on abortion-rights web sites:

They indicate that Pauline and her six children lived with her mother in Arizona while her husband was in California looking for work. They indicate that Pauline had an illegal abortion (without providing any information about a method or a perpetrator), was hospitalized, and bled to death. They add that Pauline's mother was searching for a blood donor.

With persistence, I finally tracked down Pauline Shirley's death certificate.

The death certificate straightforwardly indicated that yes, Pauline Shirley, born June 2, 1910, died in an Arizona hospital. The date disagrees slightly, with the death certificate saying August 23, 1940, rather than the August 22 that is on the prochoice sites.

One can also easily piece together from the information that Pauline was indeed living with her mother. She also wasn't living with her husband -- because she wasn't married any more. But that's really not significant. (Of course, how many children she had and what her mother was doing during Pauline's final hours won't be on a death certificate one way or the other.)

The cause of death section indicates "secondary anemia" and "uterine hemorrhage," which I would say substantiates that Pauline had bled to death.

But the abortion-rights websites deviate from the death certificate in one extremely important way:

The cause of death is noted as "incomplete abortion, spontaneous (?)" "Abortion" is the medical term for a miscarriage. So what the medical examiner was indicating when he completed the death certificate was that it looked as if Pauline had died from a miscarriage, but he wasn't 100% sure.

There is a section of the death certificate for information about external causes of death. This section is completely blank, even after an autopsy. That means that there were no signs that anybody had used instruments of any kind -- either of the medical or "coat hanger" type -- to perform an abortion on Pauline.

This doesn't rule out abortifacients, of course. Pauline might have drunk an herbal tea or used some other concoction. But in order to substantiate the assertion that Pauline died from an illegal abortion, rather than just died from complications of a miscarriage, there would have to be some documentation other than endless repetition of the same words on scads of abortion-rights web sites.

I can never say with 100% certainty that Pauline didn't use some sort of abortifacient. But by far the preponderance of evidence that I've been able to uncover is that Pauline's death was not a criminal abortion death. The most likely scenario is that somebody -- perhaps Pauline's mother -- saw the word "abortion" on the death certificate and misunderstood what it meant.

Frankly, I can't understand why they keep using Becky Bell, for whom there is absolutely zero evidence of an illegal abortion, and Pauline Shirley, for whom there is merely the inability to prove that it was not an illegal abortion. There are plenty of verifiable illegal abortion deaths with abundant documentation supporting them. I've done all the legwork already!

But nothing seems able to break into or out of the prochoice echo chamber, not even evidence like autopsy reports and death certificates.

I'd always known there was a significant problem with their claim about Becky Bell -- there is absolutely zero evidence that Becky underwent an abortion. Every piece of evidence in her death indicates that she had a miscarriage while dying of the same strain of pneumonia that killed Muppets creator Jim Henson.

Up until recently, I'd been unable to find a scintilla of information about Pauline Roberson Shirley outside of verbatim repetitions on abortion-rights web sites:

They indicate that Pauline and her six children lived with her mother in Arizona while her husband was in California looking for work. They indicate that Pauline had an illegal abortion (without providing any information about a method or a perpetrator), was hospitalized, and bled to death. They add that Pauline's mother was searching for a blood donor.

With persistence, I finally tracked down Pauline Shirley's death certificate.

The death certificate straightforwardly indicated that yes, Pauline Shirley, born June 2, 1910, died in an Arizona hospital. The date disagrees slightly, with the death certificate saying August 23, 1940, rather than the August 22 that is on the prochoice sites.

One can also easily piece together from the information that Pauline was indeed living with her mother. She also wasn't living with her husband -- because she wasn't married any more. But that's really not significant. (Of course, how many children she had and what her mother was doing during Pauline's final hours won't be on a death certificate one way or the other.)

The cause of death section indicates "secondary anemia" and "uterine hemorrhage," which I would say substantiates that Pauline had bled to death.

But the abortion-rights websites deviate from the death certificate in one extremely important way:

THE DEATH CERTIFICATE DOES NOT CONFIRM AN INDUCED ABORTION.

The cause of death is noted as "incomplete abortion, spontaneous (?)" "Abortion" is the medical term for a miscarriage. So what the medical examiner was indicating when he completed the death certificate was that it looked as if Pauline had died from a miscarriage, but he wasn't 100% sure.

There is a section of the death certificate for information about external causes of death. This section is completely blank, even after an autopsy. That means that there were no signs that anybody had used instruments of any kind -- either of the medical or "coat hanger" type -- to perform an abortion on Pauline.

This doesn't rule out abortifacients, of course. Pauline might have drunk an herbal tea or used some other concoction. But in order to substantiate the assertion that Pauline died from an illegal abortion, rather than just died from complications of a miscarriage, there would have to be some documentation other than endless repetition of the same words on scads of abortion-rights web sites.

I can never say with 100% certainty that Pauline didn't use some sort of abortifacient. But by far the preponderance of evidence that I've been able to uncover is that Pauline's death was not a criminal abortion death. The most likely scenario is that somebody -- perhaps Pauline's mother -- saw the word "abortion" on the death certificate and misunderstood what it meant.

Frankly, I can't understand why they keep using Becky Bell, for whom there is absolutely zero evidence of an illegal abortion, and Pauline Shirley, for whom there is merely the inability to prove that it was not an illegal abortion. There are plenty of verifiable illegal abortion deaths with abundant documentation supporting them. I've done all the legwork already!

But nothing seems able to break into or out of the prochoice echo chamber, not even evidence like autopsy reports and death certificates.

August 23: The Abortionist Who Turned Over a New Leaf

On August 23, 1910, 20-year-old Mrs. Louise Heinrich died in the New York apartment of Dr. Charles Buffam, age 41, and his wife, nurse Vivian Anna Buffam. I've found so much new information on Louise's death that it's getting a new post. I have found so many additional sources, in fact, that I'll not clutter the blog with them but will just list them and then post them on the Cemetery of Choice site when it's back up and running.

Andre Stapler, a

native of Austria-Hungary, had come to the United States around 1900.

He had been a drug clerk before becoming a physician. In 1910 he was

a medical student working with a Dr. Samuel Short in Harlem. All of the news coverage lists him as a doctor without putting the term in quotes, so evidently he was considered a legitimate physician by the time the unfortunate Louise came into the picture.

Louise and her husband, Samuel, traveled from Jersey City, New Jersey to the Buffams' flat at 500 West 111th Street in

New York on August 23, 1910. Sam went out walking while his wife was being attended to by Stapler. Sam returned at around 5:00 that afternoon and found his wife dead. He threatened violence against Stapler, shouting, "You murdered her!"

Somehow those present managed to calm Sam down, perhaps reminding him that everybody had the threat of arrest hanging over their heads. I've been unable to follow Sam's side of the story from this point other that eventually he was able to get his wife's body buried at St. Joseph's Cemetery in Jersey City. Per the law requiring that bodies transported across state lines be embalmed, Sam arranged for this procedure before laying his wife to rest.

In the mean time, a total of $23 worth of telephone calls (over $600 in 2020 dollars) were made from the Buffam apartment to sort out how to handle the situation. Evidently the first person contacted was a Dr. Shaw, who arrived at the flat, said that

it was a case for the Coroner, and left, refusing to sign a death

certificate. Stapler then called an attorney. He tried to slip out of the apartment but Vivian Buffum restrained him.

“Dr. Speir” – actually a drug

clerk -- came to the apartment and assured everybody that everything

would be okay. He said that he had “a pull” and that “It makes

a difference who the coroner's physician is.” Vivian Buffum finally called the coroner's office at around 9:00 p.m. -- the shift of Coroner Holtzhauser and physician Philip O'Hanlon. A clerk made an entry into the day book that Louise had died suddenly.

Though officially it was the duty of the coroner to go to the death scene to view the body, review the circumstances, and decide if the case was suspicious or not, Holtzhauser was not the most diligent of men. His qualifications for the post were dubious at best, since he had been a marble cutter before being elected. He's slid effortlessly into the role of slacker. He'd signed a paper giving O'Hanlon the authority to perform autopsies at his own discretion without getting a permit and left him and his clerks to their own devices. Holtzhauser later admitted in court that he'd never bothered with any of the five deaths that had occurred on his shift that night, neither seeing the bodies nor reviewing the paperwork. Spier had evidently understood how things worked under Holtzhauser and had waited until the 9:00 Holtzhauser/O'Hanlon shift to have Vivian Buffam make the call.

Louise's body was

taken to an undertaking establishment, where O'Hanlon performed a cursory autopsy, not even bothering to open the abdomen and examine the organs, instead just making a shallow incision in the skin. As he explained later in court, “If I felt tired I would reach a conclusion as to the cause of death as soon as possible, without making a complete autopsy, and let it go at that.” He had, he said, taken Vivian Buffum at her word when she said that Louise was a friend of hers who had come for a visit, collapsed, and died. At 10:55 that night, O'Hanlon put a slip

in Holtzhauser's box stating the cause of death as apoplexy. He made another notation in a log that Louise had died from heart disease. He then filed a death certificate with the Bureau of Vital Statistics giving the cause of

death as acute gastritis.

Vivian Buffum later testified that O'Hanlon reiterated that everything was all right and would continue

to be so as long as she kept her mouth shut. He'd written out a

statement for her to sign stating that Louise was a friend who had

come for a visit, then took ill and died suddenly.

All of the documents were filed, Louise was laid to rest, and everyone else got on with the business of life. Stapler finished medical school then quietly relocated to Chicago and set up a

reputable practice towards the end of 1913. No doubt everybody thought that the whole sordid affair had blown over. They were wrong.

In 1914, Mayor

Mitchell in New York began an investigation of the New York City

coroner's office, finding that money was being paid to officials

to falsify documents. It was then that somebody noticed that each of the three documents regarding Louise Heinrich listed a different cause of death. Her body was exhumed and an autopsy was performed

by Dr. Otto Schultze in the presence of the Hudson County Medical

Officer. Fortunately the body had been expertly embalmed and thus

could yield the necessary evidence to find the real cause of death. Louise had bled to death from abortion injuries. An investigation into the circumstances was begun and evidently the interested parties in New York pointed the finger at none other than Dr. Andre Stapler.

Stapler had not been idle in Chicago. He had become the house physician at the Plymouth Hotel at 4700 Broadway, where he lived. He also kept offices at 1060 Wilson Avenue and 59 East Madison Street, and was a staff physician at Wesley Hospital and Columbus Hospital. He was a highly respected man with wealthy, well-connected patients.

On March 12,

1915, George Freer, an official from New York City, arrived in

Chicago with a letter from the District Attorney of New York asking

for a warrant for the arrest of Anton Stapler, aka Andre Stapler.

Detectives Birmingham and Malone accompanied Freer to a building in

the Loop and arrested Dr. Stapler, who posted $7,000 bond and Stapler gave an

interview to the Chicago Tribune explaining his version of events:

In August, 1910, I was assistant to Dr. Samuel Short, who had an office at One Hundred and Fourth Street and Madison Avenue in New York. There was a Dr. W. C. Buffum who lived, as I remember it, on One Hundred and Eleventh Street, who deserted his wife and ran away with another woman. Dr. Short, who was a fellow lodge member of Buffum's, was doing some of his work. One afternoon Mrs. Buffum rang up the office and wanted somebody over there in a hurry. I went over and found this woman who is referred to, Mrs. Louise Heinrich, dead. That was my first sight of her. I called up Dr. Short. He came over, saw that the woman was dead, and notified the coroner. The body was taken to an undertaking establishment, where the corner performed an autopsy. The verdict, as I remember it, was that she died of heart disease. I never saw the coroner, and was not at the inquest, for there was no necessity of my being there. Now it seems that the easiest person to blame things on is the man out of town. Freer, who caused my arrest, asked me if I would go to New York without extradition, and I said I would. I packed up to go this morning. Apparently there is jealousy between the branches of government in New York, for Freer received a telegram from the New York district attorney that he would send one of his own men to accompany me to New York. I expect to start tomorrow at 12:40 or tomorrow night. I never had anything to do concerning any malpractice in my life except as a witness for the prosecution in the Dr. Arthur L. Blunt case.

Without first

notifying Freer, accompanied by friends and his attorney, Stapler took a taxi to the train station on Sunday

evening, March 14, 1915. He waved farewell to his friends from the

observation platform. “I'm simply going to New York like a

gentleman, without compulsion, to cut short this annoying affair,

that has grown out of some tangle of misinformation,” Stapler said

as he left. His attorney said, “My client is on his way to meet the

charges in the same manner that he will return – voluntarily and as

a free man.” One of Stapler's wealthy patients gave him a blank check to use to pay

for his defense, though Stapler said he'd not need it.

Stapler's trial

began on December 10. Vivian Buffam turned state's evidence. Her husband's whereabouts were unknown. The jury was out less

than three hours, returning at 6:00 p.m. on December 23 with a

verdict of guilty. Stapler was allowed to linger in the Tombs, with a

possible 20-year sentence hanging over his head, before finally spilling his guts about his own involvement in Louise's death, nine other doctors perpetrating abortions in the city, and the bribes they would pay to employees in the coroner's office to cover things up. Stapler said that doctors would typically pay hush money of $200 (over $5,000 in 2020 dollars) but sometimes as much as

$5,000 (over $130,000 in 2020 dollars). The money might be divided

among various doctors and clerks.

Stapler was

sentenced to Sing Sing by Justice Bartow S. Weeks on February 4,

1916. Weeks referred to Stapler's post-conviction confession as the most amazing he

had ever read, adding, “It is my belief that the defendant has for

purposes of his own, protected the men higher up in this nefarious

practice.” Stapler's assertions during his confession were

confirmed by testimony from doctors and hospital attendants –

including two doctors who were serving time in Sing Sing on

manslaughter charges related to abortion deaths.

During sentencing Weeks denounced

Stapler as “a menace to the social structure of the country. Under

the old law, a defendant convicted of the crime of which you have

been convicted would have the death penalty imposed. In my careful

consideration of your case and your statement, I have several times

come to the conclusion that such a penalty would be very appropriate

for you – not because of this one crime but because of the number

of cases that preceded it. I shall impose a sentence which will allow

you, by good behavior, to leave State's prison in time to

rehabilitate yourself and possibly become a respectable member of

society.”

Stapler's

sentence was commuted on May 15, 1920. The New York Daily News

identified him as “a leader of Sing Sing's 'idle rich.'”

His friends feted him in a hotel, with the dinner guests including

“several wealthy ex-prisoners.” He returned to Chicago, evidently having taken Justice Weeks' admonition to heart. He married a respectable young woman. He re-established a wealthy clientele, including Adolph B. Magnus, grandson of Adolphus Busch, the founder of Anheuser-Busch. He stopped dallying in criminal activities and cover-ups, instead dutifully reporting a woman who had come to him for treatment of gunshot wounds.

Stapler died of

a heart attack in his home on Lake Shore Drive on February 6,

1936. He left his widow, Helen,

and three daughters assets worth $200,000 (nearly $3.5 million in 2020

dollars).

As for what became of the widowed Samuel Heinrich, I've been unable to learn. I can't even find the cemetery where the unfortunate Louise was exhumed and given a proper autopsy. She was reburied in a different cemetery in a different county.

- “Mystery Arrest on Old Charge,” Chicago Tribune, March 13, 1915

- “'Mystery Case' Veil Removed,” Chicago Tribune, March 14, 1915

- “Stapler Leaves to Face Charge,” Chicago Tribune, March 15, 1915

- “Charges Physicians Concealed a Crime,” New York Times, December 11, 1915

- “Dr. O'Hanlon Named in Fatal Operation Trial,” New York Tribune, December 11, 1915

- “O'Hanlon Accused in Woman's Death,” The New York Sun, December 11, 1915

- “Court Hearing for Dr. O'Hanlon Denied,” The New York Sun, December 14, 1915

- “Says Coroners Rely on Clerks' Reports,” New York Times, December 14, 1915

- “Dr. O'Hanlon Denies Hiding Death Cause,” New York Times, December 22, 1915

- “Dr. Stapler Found Guilty,” New York Times, December 24, 1915

- “Stapler Found Guilty,” New York Sun, December 24, 1915

- “Coroners Named in N. Y. Graft Charges,” Middletown Daily Times-Press, January 14, 1916

- “Detectives Trail Malpractice Band Stapler Accuses,” New York Evening World, January 14, 1916

- “Stapler Reveals Malpractice Ring,” New York Times, January 14, 1916

- “Facts of Doctors' Crime Trust to Go to Grand Jury,” New York Evening World, February 4, 1916

- State of New York Executive Chamber document dated May 15, 1920

- “Sing Sing Bows Farewell to Two Noted Prisoners,” New York Daily News, May 26, 1920

- “Engagement,” Chicago Tribune, May 11, 1922

- “Find Furrier Slain in North Side Mystery,” Chicago Tribune, November 7, 1930

- “Dr. Andre L. Stapler Dies; Physician Here 20 Years,” Chicago Tribune, February 7, 1936

- “$15,647 Owed to Doctor; Accounts Sold for $5,000,” Chicago Tribune, January 28, 1937

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)