Ollie Whisks Ethel Away

Ethel Irene Smith, age 20, lived with her father, William Archie Smith, in Guilford County, about six miles north of Greensboro, North Carolina. At about 6:30 pm on Monday, November 5, 1934, 35-year-old Ollie Parish pulled up outside the Smith home and honked his horn. Parish, who lived only about 3/10 of a mile from Ethel, had been "going with her" for about two and a half years, meeting her outside her home about weekly. He'd only ever gone to her home to visit her once or twice in all that time. At the sound of Ollie's horn, Ethel put on her cloak and hat and rode off with her sweetheart.

The couple drove to the home of Ethel's sister, Golda Smith Brewer, in Greensboro, arriving at around 8:30 that evening though the drive from Ethel's home was only about 15 minutes. The couple went in and chatted with Mrs. Brewer for about fifteen minutes before Ollie left, telling Ethel he'd stop by to see her on Tuesday.

Ethel slept over Monday and Tuesday nights. Ollie did not stop by as he had promised.

Ethel Takes Ill

On Wednesday morning, about about 6 a.m., Ethel called out for her sister. Mrs. Brewer found Ethel to be in severe pain, so she summoned Dr. W. P. Night.

Dr. Knight arrived about an hour later and examined Ethel. He determined that she was laboring to expel a fetus as a result of instruments used on her to cause an abortion. On his advice, Ethel was taken to St. Leo's Hospital by ambulance.

Doctors found a decomposed fetal skeleton in Ethel's vagina, causing blood poisoning. They also performed a curettage to remove any tissue from her uterus.

Ethel would remain hospitalized until her death on at 7 a.m. on November 29 from septic pneumonia. Strangely, there was no manner of death marked on her death certificate.

On November 12, police arrested Ollie Parish. While he was in jail, Ethel's brother-in-law, Eli Brewer, came to visit him and reported that Ollie said, "I was going to marry her; I intend to marry her."

Ethel's Story

Minnie D. Hinton was a county case supervisor. On Friday, November 9, she visited Ethel in the hospital and found her gravely ill. She visited Ethel several more time, including on November 16. Armed with information passed along to her, she knelt by Ethel's bed.

Minnie D. Hinton was a county case supervisor. On Friday, November 9, she visited Ethel in the hospital and found her gravely ill. She visited Ethel several more time, including on November 16. Armed with information passed along to her, she knelt by Ethel's bed.

Ethel told her that Ollie was the father of her baby, and that at his insistence, over her objections, he'd taken her to Dr. Stewart.

Ollie, she said, brought her to Stewart's office on three time, the last visit being Monday, November 5. That evening Stewart had put her on a table and inserted a tube into her vagina, telling her to leave it in place until Tuesday night. He admonished her that if anybody asked her what had taken place, she was to say she had taken quinine.

Later that evening Mrs. Hinton got a call to return to the hospital. A stenographer was there, along with the stenographer's husband and a man named Mr. Ballinger. She questioned Ethel while the stenographer wrote the conversation down in shorthand.

Ethel restated that she was pregnant by Ollie Parish and that he had insisted on an abortion.

The first visit to Stewart, she said, had been on October 1, when "He put me on the table and used an instrument to open me up." He told Ethel to return on Saturday night "and he would do the rest."

Ethel gave no details on what happened on the second visit, about two weeks later.

On the third and final visit, Monday, November 5, and "put a tube in me" with instructions "to take it out the next night at the same time. I did so, and that was when I was taken so sick."

Ollie's Story

Ollie later testified that he had known Ethel Smith since she was a child. He denied ever engaging in sexual intercourse with her, but said, "I was in love with her. I think she was fond of me. We were not particularly engaged. I did not have a job sufficient to marry. We never discussed marriage."

He admitted to driving Ethel to her sister's home but said that they'd arrived at about 7:00, and that the trip had been at Ethel's request. "I did not know that she was pregnant. I did not take her to Dr. C. C. Stewart's office that night, or at any other time."

He denied having told Ethel's brother-in-law that he had intended to marry Ethel.

The Other Party

Dr. Charles C. Stewart, a Black doctor, had an office in the Stewart Building, on East Market Street in Greensboro. He, like Ollie Parish, was arrested November 12. He was released on $2,500 bond.

He testified, "I did not, during October or November, 1934, or at any other time, insert any instrument or tube, prescribe any medicine, or give any advice to a white woman named Ethel Smith for the purpose of causing her to have an abortion. I did not attend her in any capacity, nor did I have any conversation with her about quinine."

He did say that a white woman, who resembled the photograph of Ethel Smith, did visit his office on the evening of October 15. "She seemed to be excited. I asked her what I could do for her. She said that she was pregnant and asked me if I could do something for her. I told her, no. She said somebody must do something for her. I said, I am sorry, and I have not seen her since."

He also said that he had never seen Ollie Parish until the preliminary trial in the abortion case.

The court document mentioned that "There was evidence tending to corroborate the testimony of the defendant C. C. Stewart. There was also evidence tending to show that his reputation in the city of Greensboro, both as a man and as a physician, is good.

The Outcome

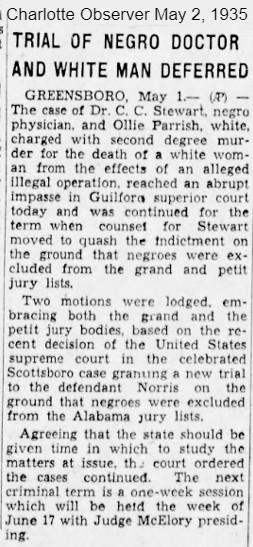

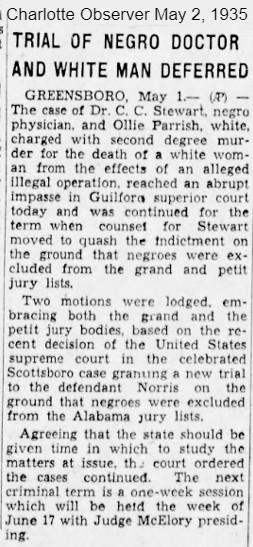

The two men were originally charged with second-degree murder.

The two men were originally charged with second-degree murder.

The trial brought little publicity, mostly getting mention in summaries of whatever was happening in court that week. An exception was an article noting that Stewart's attorney had peremptorily challenged a Black man on the jury list, after having quashed the indictment the previous year because there were no Black men in the jury pool. Stewart and Parish eventually managed to seat a jury with two Black men and the case could proceed.

There was also a moment of drama when Dr. Charles E. Moore, a defense witness, was charged with contempt when he showed up for court so intoxicated that he could not testify.

Both men were found guilty of manslaughter. Stewart was sentenced to 7 - 12 years, Parish 12 - 15 years. The men appealed on the grounds that Ethel's statement, taken November 16, could not be considered a deathbed statement because it was not clear at that time, 13 days before her death, that Ethel was certain to die shortly. They won their appeal for a new trial. Stewart was released on a bond of $5,000 but Parish remained in jail because he couldn't raise his $7,500 bond.

I haven't seen documentation of a new trial, and as of September of 1936, Stewart was still a free man and practicing medicine, as evidenced by a lawsuit filed against him as a general surgeon.

Sources:

- North Carolina Standard Certificate of Death District 41-95 No. 620

- "Jailed for Death of Young Woman," (Raleigh, NC) News and Observer, December 1, 1934

- "Trial of Negro Doctor and White Man Deferred," Charlotte (NC) Observer, May 2, 1935

- "Challenges Negro on Guilford Jury," (Raleigh, NC) News and Observer, February 5, 1936

- "Orders Doctor Jailed on Contempt Charge," (Raleigh, NC) News and Observer, February 7, 1936

- "Physician is Freed Following Apology," News and Observer, February 8, 1936

- "Dying Statement Convicts Doctor," (Raleigh, NC) News and Observer, February 10, 1936

- "Convict Two of Manslaughter," Charlotte (NC) Observer, February 10, 1936

- State v. C. C. Stewart and Ollie Parish, Filed 30 June, 1936, page 1 and page 2

- "Negro Is Suing Hospital For Amputation Of Foot," Charlotte (NC) Observer, September 3, 1936

- "Choice and Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and Welfare," Johanna Schoen, University of North Carolina Press, March 2006

- Genealogical online searches determined first name of sister

Virginia Hopkins Watson, an Illinois native, had been on a record-setting relay swimming team with Esther Williams in 1939. Virginia had herself set the world's fifty-meter record in 1938.

Virginia Hopkins Watson, an Illinois native, had been on a record-setting relay swimming team with Esther Williams in 1939. Virginia had herself set the world's fifty-meter record in 1938.