|

| Carolina Gutierrez |

When they found out that Carolina was pregnant, Jose later said, they were happy to be having a baby together. But 20-year-old Carolina started having second thoughts because of the family's finances. She proposed an abortion. Jose was against the idea.

Without saying anything to her husband, Carolina had a friend drive her to Maber Medical Center, a storefront clinic stuck between a cigar factory and a bar in Miami for an abortion on December 19, 1995.

The evening after her abortion, Carolina had pain in her chest and abdomen. She staggered about the house, barely able to walk. She called the clinic for help, but whoever answered the phone hung up on her.

Over the next two days, Carolina left messages on the clinic answering machine, but nobody returned her calls.

The evening after her abortion, Carolina had pain in her chest and abdomen. She staggered about the house, barely able to walk. She called the clinic for help, but whoever answered the phone hung up on her.

Over the next two days, Carolina left messages on the clinic answering machine, but nobody returned her calls.

On December 21st, she could hardly breathe, so her family called 911. She arrived at the emergency room of Jackson Memorial Hospital already in septic shock. Whoever had done the abortion had poked two holes in her uterus. Carolina underwent an emergency hysterectomy at the hospital to try to halt the spread of infection from her perforated uterus. She was put into the intensive care unit, where she battled for her life against the raging sepsis. She was on a respirator, with her fingers and feet going black with gangrene as doctors pumped antibiotics into her.

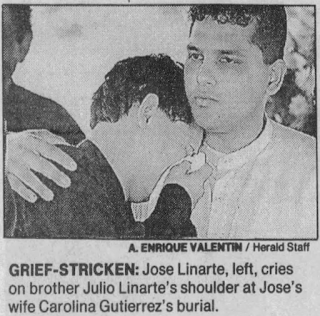

Relatives cared for her children, a five-year-old girl and a two-year-old boy, while Carolina's husband spent as much time as he could by her side. "I can't sleep. I try to take my mind off it, but it's impossible," he told the Miami Herald.

Carolina's 21st birthday came and went as she lay in the ICU. Doctors fought to help the young woman to gain enough strength to undergo amputation of her gangrenous limbs. Finally doctors took off both legs below the knee. But despite the hysterectomy, the amputations, and all their other efforts, Carolina died on February 5, 1996.

He remained bewildered about the abortion. "We wanted a child. That's all we talked about. We even bought clothes for the baby."

Relatives cared for her children, a five-year-old girl and a two-year-old boy, while Carolina's husband spent as much time as he could by her side. "I can't sleep. I try to take my mind off it, but it's impossible," he told the Miami Herald.

Carolina's 21st birthday came and went as she lay in the ICU. Doctors fought to help the young woman to gain enough strength to undergo amputation of her gangrenous limbs. Finally doctors took off both legs below the knee. But despite the hysterectomy, the amputations, and all their other efforts, Carolina died on February 5, 1996.

"I have lost the love of my life," Jose said in a press conference. "I'm heartbroken. They have taken my happiness away."

He remained bewildered about the abortion. "We wanted a child. That's all we talked about. We even bought clothes for the baby."

When an attorney acting on behalf of the motherless children tried to get Carolina's medical records so that he could sue the clinic. The clinic owners simply shut the place down and refused to allow any contact. Maber Medical Center first began operating without a license in the 1980s. When they got caught in 1991, they simply called and asked for a license. The license was issued on request.

Maber Medical Center passed all of their inspections after licensing. This should come as no surprise since thanks to abortion-rights lobbyists, an annual "inspection" consisted of six questions answered from examining paperwork. Inspectors would verify that the clinic posted its license, kept patient files, had arrangements (on paper at least) for medical waste disposal, and had at least one doctor's name on file. There was no examination of the premises or equipment or review of staff training.

A Miami Herald reporter went to the closed-down clinic and peered through a window:

A narrow and dingy waiting room, little more than a corridor with chairs facing each other, can be seen.... The rules are posted. No lying down. No children in the waiting room. Everyone shows up at 9 a.m. You take a number off the peg on the wall, and you wait your turn."

Maber had only one doctor officially on staff, Dr. Luis J. Marti. Because officials were unable to get any records from the clinic they were unable to determine if he had actually been the one who performed the fatal abortion.

While investigating the clinic, owned by Maria Luisa and Roque Garcia, officials noted that although Carolina could not read English, her only consent form was in English -- and the line for her signature was blank. She had paid $225 in cash for the abortion that took her legs and her life.

Dade County Right to Life raised the money to cover funeral expenses and to help Jose to care for the children. As for abortion rights activists, one of the wrote a letter to the Miami Herald advising women to consult with Planned Parenthood and the National Abortion Federation -- organization whose affiliates and members have committed enough acts of malpractice to prove themselves untrustworthy. The Miami Herald also put in a good word for NAF with a little inset box in an article telling readers about NAF's stated standards and provided a toll-free number for women who would be left unaware that they were calling an organization that had the likes of Abu "The Butcher of Avenue A" on its membership rolls. And Representative Ben Graber, chairman of the Florida House Health Care Committee, opposed tightening abortion clinic regulations beyond the cursory check of paperwork. Any additional regulations, Graber said, would just make abortion more expensive and limit options for low-income women. Graber, like many prochoice activists after him, insisted that the best way to improve abortion safety would be to just let the doctors do as they please because this would take off the pressure. Exactly how that would motivate them to provide better care remains a mystery.

Watch Access to Horror on YouTube.

Sources:

- "Abortion patient ill; clinic under scrutiny," Miami Herald, January 26, 1996

- "Infection kills abortion patient," Miami Herald, February 6, 1996

- "Raging infection takes life of Dade abortion patient," Miami Herald, February 6, 1996

- "Infected woman dies after abortion," News Press, February 6, 1996

- "Carolina Gutierrez Services Set," Miami Herald, February 8, 1996

- "Avoid abortion tragedies," Miami Herald, February 8, 1996

- "Abortion clinic regulations often found to be lax," Miami Herald, February 18, 1996

No comments:

Post a Comment