Would Prince stop perpetrating abortions if they were recriminalized? It's difficult to say. I've found no evidence that he was a criminal abortionist before Roe, and he does not appear to be flagrantly breaking the law now, so he's not a likely candidate for taking up a life of crime. However, abortion has become his livelihood, so recriminalization would leave him in dire financial straights, as well as with an enormous void in his life. This is something we need to prepare for when legal protection is restored to the unborn and their vulnerable mothers. Fortunately, many abortionists are up in years (Prince himself graduated from medical school in 1960), so retirement will be a tempting option and might be enough to take many of them out of circulation.

Wednesday, May 31, 2023

May 31, 1986: Death in Dallas

Would Prince stop perpetrating abortions if they were recriminalized? It's difficult to say. I've found no evidence that he was a criminal abortionist before Roe, and he does not appear to be flagrantly breaking the law now, so he's not a likely candidate for taking up a life of crime. However, abortion has become his livelihood, so recriminalization would leave him in dire financial straights, as well as with an enormous void in his life. This is something we need to prepare for when legal protection is restored to the unborn and their vulnerable mothers. Fortunately, many abortionists are up in years (Prince himself graduated from medical school in 1960), so retirement will be a tempting option and might be enough to take many of them out of circulation.

May 31, 1983: Would a Proper Screening Have Saved Maureen's Life?

|

| Maureen Tyke |

Maureen Tyke, a 21-year-old North Huntington, Pennsylvania resident, was in Florida visiting a friend when she went to Aware Woman Clinic in Melbourne for a safe and legal abortion.

The abortion was performed by Dr. John Bayard Britton on Friday, May 27, 1983. The clinic records indicate that Britton noted that Maureen had a complete double uterus and cervix. Nobody noted anything else unusual.

About 24 hours after her abortion, Maureen developed nausea, vomiting, and chills. She felt extremely ill.

Doctors at the hospital contacted the clinic, which to their credit provided copies of Maureen's records.

Doctors at the hospital contacted the clinic, which to their credit provided copies of Maureen's records. Doctors at the hospital performed a complete hysterectomy on Maureen to try to remove what seemed to be the source of the infection. Their efforts were in vain. The raging infection led to septic shock and heart failure. Maureen died at 4:15 on the morning of May 31.

The autopsy found that Maureen had "florid myocarditis, probably of viral etiology [a serious viral infection of the heart]."

The medical examiner added, "The intensity of this myocarditis should indicate that the young woman was very ill and there should have been some signs or symptoms of serious illness at the time she was being prepared for the abortion."

However, as the autopsy had noted, nobody at the clinic had noticed that Maureen was very ill and in no condition for elective surgery. It can't be said for certain that an adequate physical examination and a referral for proper care could have saved Maureen. We can only know that they didn't happen.

- Transcript of autopsy provided by Forerunner.com

- "Clinic's patient dies 4 days after abortion," Florida Today, June 1,1983

- "Police investigating death after abortion," Orlando Sentinel, June 2, 1983

- "Police wait on results of autopsy," Orlando Sentinel, June 9, 1983

- "Heart malady blamed in abortion fatality," Florida Today, June 9, 1983

- "Pro-life activists mourn woman dead a decade," Florida Today, June 1, 1993

Monday, May 29, 2023

Rosa's Premature Celebration

According to a Chicago Sun-Times article, Rosa Naperstek-Taft, a 28-year-old attorney who "was at the forefront of the fight for legalized abortion," "gathered with some friends who had had dangerous illegal abortions in the past" the night prior to her abortion, and, Taft said, "We all rejoiced that night about how I would be able to get a safe, legal one."

Her celebration was premature.

She underwent the abortion in January of 1973 at Planned Family Center in Detroit. She paid $150 and was told that the abortion would be performed by "Dr. Lee." It was actually performed by Dr. Ming Kow Hah, dubbed "physician of pain" by the Chicago Sun-Times.

Rosa said that she screamed in pain during the abortion, and a staffer responded by stuffing a tampon in her mouth.

The abortion was so badly botched that Rosa lost all her reproductive organs and her spleen. She had to undergo a colostomy and tracheotomy, and suffered damage to her heart, lungs, kidneys, and vocal cords. She was hospitalized for eight months, with three of those months spent in intensive care.

After her injuries were repaired, Rosa had to undergo intensive therapy to learn to walk and talk again. She was unable to work for a year.

Rosa said, "I don't have my normal body. My abdomen looks like a sky map of the Grand Canyon. ... My voice is totally changed, and I have a lot of psychological scars that will be with me forever."

She settled for $600,000 out-of-court.Rosa's suit also charged Highland Park Hospital with negligence in allowing Hah hospital privileges and in "permitting Dr. Hah to operate as an abortionist and advertise and permit him to hold himself forth as a member in good standing and a member of the staff so as to attract the public to the abortion facilities."

Watch Premature Abortion Celebration on YouTube.

Sources:

- "Dr. Ming Kow Hah: Physician of Pain," Chicago Sun-Times November 15, 1978

- Wayne County Circuit Court Case No. 73 250 920 CM

May 29, 1988: The "Texas Gosnell" Lets Teen Die

Denise Montoya was fifteen years old when her parents brought her to Women's Pavillion in Houston for an abortion on May 13, 1988. Denise was 25 1/2 weeks pregnant.

The abortion was performed by Douglas Karpen, an osteopath.

Denise suffered severe bleeding, and was admitted to Ben Taub hospital. Her condition deteriorated, and she died on May 29, 1988.

Her parents filed suit against Karpen and the clinic, saying that they had failed to adequately explain the risks of the procedure, and had not provided consent forms, or had the parents sign any informed consent document, prior to the fatal abortion. They asserted that had they known how dangerous abortion is that late in the pregnancy they never would have subjected their daughter to the procedure.

According to their 1991 Annual Report, Women's Pavillion was a National Abortion Federation member.

Karpen was also sued over the March 14, 1989 death of Glenda Davis.

Karpen has been dubbed "the Texas Gosnell" by prolife activists after his employees came forward to report appalling behavior including delivering babies alive then killing them.

Watch "Not Warned of Risks Before Late Abortion" on YouTube.

Sunday, May 28, 2023

Coat Hanger Abortions: How True an Image?

One of the strongest images in the abortion-advocacy arsenal is that of the desperate woman who, unable to arrange a legal abortion, harms or even kills herself in an attempt to do the abortion herself. There is no denying that some pregnant women attempt, and even die from, grotesque attacks on their own reproductive organs. But is this phenomenon really a sociological problem, caused by lack of "access" to legal abortion? Or is there something else going on?

Both anecdotal and statistical research show that most women who have trouble arranging a professional abortion will quickly adapt to the pregnancy and even come to welcome the birth of the baby. Dr. Aleck Bourne, who in 1938 successfully fought the British law against abortion, said in his memoir (A Doctor's Creed: The Memoirs of a Gynaecologist):

"Those who plead for an extensive relaxation of the law [against abortion] have no idea of the very many cases where a woman who, during the first three months, makes a most impassioned appeal for her pregnancy to be 'finished,' later, when the baby is born, is thankful indeed that it was not killed while still an embryo. During my long years in practice I have had many a letter of the deepest gratitude for refusing to accede to an early appeal."

One of the observations of the 1955 Planned Parenthood conference on abortion was that given the chance to work through their problems, most women would reject abortion. The conference further noted, and Nancy Howell Lee's research (The Search for an Abortionist) confirmed, that the situation before legalization was not one of hoards of women wielding coat hangers on themselves. Most women who requested abortion rejected the option on giving the matter more thought. Those who persisted typically managed to arrange an abortion by a physician or a trained para-medical professional with a physician providing backup. How, then, do we explain the women who turned up in emergency rooms and morgues, horribly injured by aggressive attacks on their own gravid wombs?

In exploring the issue of dangerous self-abortion attempts, we have to take into account the fact that these self-abortion attempts very rare. Nancy Howell Lee's research found that dangerous self-abortions were attempted by about 2 percent of the women she surveyed. The Planned Parenthood conference estimated that dangerous amateur abortions (self-attempted or attempted by obviously unqualified others) accounted for perhaps 8 percent of illegal abortions. But even though the self-aborting woman was a rare case, advocates of legalization held them up as proof that society has an obligation to make professional abortion readily available.

We also have to take into account the fact that such abortion attempts persist, even with legal abortion readily available. This is one of the dark, inexplicable secrets of the abortion advocacy movement. In 1982, CDC staffers published "Illegal-Abortion Deaths in the United States: Why Are They Still Occurring?" in Family Planning Perspectives. They noted that illegal abortions ranged from "self-help" abortions done by women who reject the medical establishment, to the stereotypical "coat hanger" abortions. They concluded that women seek illegal abortions for "idiosyncratic" reasons, and dropped the issue.

The "self-help" abortions do sometimes result in deaths. As recently as 1994, a young woman died as a result of attempting to abort with pennyroyal tea. But this was not a case of a massive attack on the reproductive tract; this woman was using what she thought was a safe, "gentle," and "natural" process. Such an attempt is a far cry from Drano douches and rusty coat hangers.

Why is it that some women, with legal abortion readily available, and with information on "self-help" abortions available, will viciously attack their own bodies, or allow someone else to do so? To say that they were simply trying to dislodge a fetus is facile; there are far safer, less painful means of trying to get rid of a fetus. There is obviously something else going on.

The most coherent explanation for these self-mutilative abortions is evident in the very damage that they do to the woman's body. These self-abortion attempts are most likely manifestations of self-injury, a phenomenon commonly seen in women (and occasionally men) with certain types of mental illness.

Most kinds of self-injury are cuts, bites, and burns with cigarettes. The injuries range from mild bruises and superficial scratches to amputation of limbs, putting out eyes, or castration. Some of the reasons people self injure include reducing tension, expressing emotional pain or rage, self-punishment, manipulativeness, feeling a sense of control of one's body, or expressing or repressing sexuality.

People who self-injure tend to be depressed, very sensitive, and acutely tense. One researcher (Herpertz) believes that some stress increases the anxiety and tension to an overwhelming state. The act of self-injury releases the tension. Some researchers believe that this may be due to brain imbalances; others think it is a learned behavior caused by childhood abuse and/or trauma.

Two researchers, Haines and Williams, found that self-mutilators tend to cope with problems by avoiding them, rather than with problem-solving techniques. This might explain why women who might otherwise self-mutilate will attempt a violent self-induced abortion rather than calmly assess how to arrange a legal abortion or adapt to the pregnancy and arrival of a new baby.

There are common characteristics to people who self-injure. They tend to dislike themselves, be hypersensitive to rejection, be highly impulsive, act based on their immediate emotions, not plan for the future, be depressed and/or suicidal or self-destructive, and be lacking in adequate coping skills. Now, how does all this relate to "coat hanger" abortions?

Observations on the traits and behaviors of people who self-harm are in keeping with the research by Nancy Howell Lee on women who sought and obtained pre-legalization abortions. She found that the women who attempted aggressive self-induced or other obviously dangerous abortions tended to be self-destructive, and to themselves view the abortion attempt as more of an attack on themselves than as an attempt to dislodge the fetus. Case reports I've read on self-induced abortion attempts also found that the women did not tend to perceive the fetus as "other," but as an embodiment of their own hated selves. In these cases, the attempt to self-abort was a bizarre attempt at self-destruction.

Given what we know about self-abuse, and about "coat hanger" abortions, it is reasonable to conclude that aggressive and dangerous self-abortion attempts are best understood as a type of self-mutilation, and not as rational attempts to end an ill-timed pregnancy. The best service we can do, therefore, to women who might attempt such abortions is to provide the best supportive and psychiatric care to self-injurers, and to ensure that professionals who work with these women are aware that a self-induced abortion might be attempted by these patients should they encounter an unintended or otherwise stressful pregnancy.

Legalizing abortion did nothing for these women; it merely swept the problem under the rug. We need to bring it back into the open and address it rationally and compassionately.

May 28, 2010: Fatal Referral After Fetal Demise

Operation Rescue obtained documents from a 2011 medical malpractice/wrongful death lawsuit filed by the family of Rebecca Charland, whose OB/GYN referred her to her death in the spring of 2010.

|

| Washington Surgi-Clinic |

|

| Dr. Cesare F. Santangelo |

Saturday, May 27, 2023

May 27, 1952: Hollywood Socialite's Body Dumped in Alley

|

| Patricia Layne Steele |

Victor refused to view his daughter's body in the morgue, but did identify her belongings. He said that he believed that Patricia had eloped to Tijuana with an unidentified serviceman in a blue uniform the previous November. She had made trip to Hawaii shortly thereafter Victor believed that the trip had been a belated honeymoon.

.png) After a promise that an arrest was pending, all mention by the police about the fatal abortionist disappeared from news coverage until November of 1944. Then, police announced that a Los Angeles osteopath, Dr. Frank S. Bunker, was being investigated for four abortion deaths and a kidnapping charge. Only two of the four women, Patricia and Jessie Neidt, were named in news coverage.

After a promise that an arrest was pending, all mention by the police about the fatal abortionist disappeared from news coverage until November of 1944. Then, police announced that a Los Angeles osteopath, Dr. Frank S. Bunker, was being investigated for four abortion deaths and a kidnapping charge. Only two of the four women, Patricia and Jessie Neidt, were named in news coverage.Sources:

- "Patricia Steele Enlists," Los Angeles Times, May 2, 1944

- "Socialite Found Dead in Alley," Evening Vanguard, May 27, 1952

- "Operation Blamed in Girl's Death," Hollywood Citizen-News, May 27, 1952

- "Hollywood Play-Girl Found Dead In Alley; Said Victim Of Abortion," Lancaster (PA) Intelligencer Journal, May 28, 1952

- "Trace last days in life of socialite," Los Angeles Daily News, May 28, 1952

- "Socialite's Surgery Death Probed," Oakland Tribune, May 28, 1952

- "Wealthy Woman Dies in Mystery," Los Angeles Times, May 28, 1952

- "Illicit Surgery Death Quiz," San Francisco Chronicle, May 28, 1952

- "New Clues Found In Steele Death," Visalia Times Delta, May 29, 1952

- "$10,000 Ring Linked to Woman's Mystery Death," Los Angeles Times, May 29, 1952

- "Beauty's Death Agony Bared; Reported Wed," Los Angles Mirror, May 29, 1952

- "Seek Nurse in Fatal Abortion on Socialite," Los Angeles Daily News, May 29, 1952

- "Socialite's body taken from morgue," Los Angles Daily News, May 30, 1952

- "Police Check Phone Calls for Fatal Surgery Doctor," Los Angeles Times, May 30, 1952

- "Rites Arranged for Society Beauty Found Dead in Alley," Hollywood Citizen-News, May 31, 1952

- "Secrecy Cloak Put on Rites for Patricia Steele," Los Angles Times, May 31, 1952

- "Detectives Cloak Clues in Patricia Steele Death," Los Angeles Times, June 1, 1952

- "Police Say Doctor In Patricia Steele Death Case Known," Hollywood Citizen-News, June 2, 1952

- "Police on Trail of Suspect in Patricia Steele Death," Los Angeles Times, June 2, 1952

- "Arrest Near In Steele Death," Redlands (CA) Daily Facts, June 2, 1952

- "Inquest Set for June 10 in Patricia Steele Death," Los Angeles Times, June 3, 1952

- "Quiz Osteopath in 4 Illegal Surgery Deaths," Hollywood Citizen-News, November 6, 1954

- "Doctor Quizzed on 4 Women's Deaths," Los Angeles Times, November 6, 1954

Friday, May 26, 2023

May 26, 1950: Lay Abortionist Blames Death on Phlegm

Joy Malee Joy, 25 years of age, was an employee of Pratt Union in Cunningham, Kansas. She lived with her mother, Inez, identified in news coverage as Mrs. Roy G. Lewis, and her 6-year-old daughter, Vicky Joy. Joy was a former resident of Hutchinson and Medora, and had graduated from Buhler HS in 1942. She had divorced Vicky's father five years earlier

On May 26, 1950, ambulance driver Phil Johnson of got a call of a sick woman at the home of Annas Whitlow Brown. Brown had lived 25 years in Hutchinson, and was the mother of two grown daughters.

When Johnson arrived, he was directed through Brown's garage to the basement, where he found a woman lying on a bed on the large bedroom. She appeared to be dead. The bedspread was stained. The woman was Joy Malee Joy. Johnson transported her to Grace Hospital, where she was pronounced dead on arrival.

An inquest into Joy's death was held at Johnson and Sons Funeral Home.

Deputy Sheriff Gene Schroder and Captain John Robinson said that they went to Brown's home at around 9:00 pm. Brown showed them a first floor bedroom and said that this was where Joy had lay down. The police said they told her they knew better, whereupon Brown led them to the basement. They found two bedspreads, still damp, hanging in the utility room.

They said that Brown told them that Joy had suffered a coughing spell so she'd given the young woman a peppermint and a glass of water.

In Joy's purse police found a business card for Annas Whitlow Brown and her phone number. On the back, in pencil, was nurse Margaret Dowdy's name, address, and phone number.

Pathologist Dr. L. C. Murphy performed an autopsy, along with coroner Dr. G. A. Chickering. Murphy testified that "there were two findings. First the examination showed a five months pregnancy. Second there was evidence of instrumentation. There was evidence of an attempt at an abortion." This included tearing of the placenta and uterine bleeding. He believed that Joy had died from either blood loss or asphyxiation. At the time of her death Joy had been suffering from a cold which could have been a contributing factor. "An acute cold, coughing ... could have resulted in death if weakened by anesthetic or loss of blood."

Murphy said that the abortion had only been initiated, not completed. The attempt, however, had triggered heavy bleeding. "There was no way to tell how much loss of blood was suffered." Murphy could not decide if death had been caused by choking on mucus and vomit or by blood loss. Dr. Chickering added that in his opinion, "death was caused by an operation or the circumstances surrounding it."

A man named Frank Annett, from Pratt, testified that he knew Joy, who had approached him about a month earlier and "intimated she was pregnant." She had not, he testified, said anything about an abortion. About a week later, he testified, Joy had come to him wanting to borrow money.

Joy's mother wept when recalling that Joy had called her on Friday, saying that she was going to a shower for a friend and would be getting home late. She said that she hadn't known that her daughter was pregnant. Joy had been suffering a severe cold but was feeling better on Friday.

Nurse Dowdy, who had practiced for 35 years, testified that she had taken care of patients in her home for Brown. When asked if she knew the victim, Dowdy replied, "I never heard of Joy Malee Joy." She said that when Brown referred patients to her, she identified them from their home towns. Thus Joy Joy was "the girl from Pratt." Dowdy said that she'd also been told that "the girl from Pratt" had a daughter living in Cunningham with her grandmother. Dowdy said that Brown had contacted her about two weeks earlier, then was called on May 26 and told that "the girl from Pratt" would be coming to stay with her for a few days. "She called again in a few minutes, about 15 minutes, and said the girl was sick and had turned blue and would I come right out."

Dowdy said that by the time she arrived at Brown's house, "the girl from Pratt" had already been taken away. Dowdy went to the basement, where Brown had a rec room, a utility room, and two bedrooms. One bedroom had an attached bathroom.

"Mrs. Brown told me the girl had asked to use the bathroom, had a severe coughing spell and then asked to lie down on the bed. She gasped a few times and was gone. There was a large red spot on the bed."

Dowdy said that she had not been specifically told why Joy was at Brown's home, but believed it was for an abortion. When asked if she was an abortionist, she replied, "Oh no. I've never done an abortion. I just do the cleaning up, the after care." The women would stay with her for three or four days. "I keep them in bed and feed them. I determine when they are ready to go." She said that the "girls" would pay her ten dollars a day. She said that the only medications she would administer were aspirin and laxatives. When asked if she'd call a doctor if one of the "girls" got sick, Dowdy said, "I've never had that happen.

Brown was charged with first degree murder. She remained free on $7,500 bond until the trial. Her defense asserted that Joy had not bled to death but that "death resulted from a collection of mucus in her trachea." Brown convicted of manslaughter by abortion.

After the conviction, Inez filed $15,000 suit against brown on behalf of Vicky.

Sources:

- "Charge Manslaughter," Hutchinson (KS) News-Herald, May 28, 1950

- "Claim Abortion Was Not Cause of Death," Hutchinson (KS) News, November 20, 1950

- "$15,000 Suit Against Annas Brown," Hutchinson (KS) News-Herald, September 8, 1951

- Joy v. Brown, 173 Kan. 833 (1953)

May 26, 1915: Bullet in the Head Fails to Distract From Abortion

|

| Anna Johnson |

Dr. Shaver told police, "Miss Johnson came to my home eight days ago. She said she was from Ludington, Michigan. She wanted work and I employed her as a maid for $5 a week. She spoke to me only a few times and never mentioned her relatives or anything about being despondent."

Shaver continued, "I sent her to a drug store for cotton late yesterday afternoon, and when I returned I went out to make a professional call. When I got back at 6 o'clock in the evening Harvey told me that he had found her dead body in my son's room."

Another witness, nurse Anna Bratzenberg, would later corroborate part of Shaver's story at the inquest. She said that she had gone to Shaver's house for an appointment at 5:30 the evening in question. Bratzenberg waited about fifteen minutes until Shaver arrived home. "Harvey whispered something to her. She looked scared. I asked her what was the trouble and she said, 'A girl roomer has just blown her brains out.' I didn't want to get mixed up in something like that, so I left."

Not a Suicide

|

| Dr. Eva Shaver |

At first, Coroner's Physician Reinhart issued a statement that Anna, about six weeks into pregnancy, had died from the results of an abortion perpetrated two days earlier. He noted that there was very little blood from the bullet wound, indicating that it was inflicted after death. Later he changed his mind, and decided that there was enough blood from the head wound to indicate that Anna had been alive when the bullet was fired into her brain. Anna was already moribund when the shot was fired.

Whether the shot was fired before of after Anna's heart had stopped beating, the fact that the gun was in Anna's left hand but the bullet wound on the right side, it was clear that she had not shot herself. The coroner's jury concluded that the shooting had been an attempt to hide the fact that an abortion was the true cause of death.

The coroner's jury was unable to determine which of their three suspects fired the shots: Clarence, Dr. Shaver, or Willis Harvey.

Investigators tore up the floorboards in the house, searching for the remains of aborted babies.

The Motive for the Abortion

|

| Anna Johnson and Marshall Hostetler |

Don't do anything rash, and when you get married, get married right. You have oceans of time for this married bliss stuff. Don't get married too soon; it will mean good night to all your times.

|

| Clarence Shaver |

|

| Shaver's "Little Red and White Pills" |

Hostetler reported this failure to Clarence, who showed him letters purportedly from satisfied customers. He told Hostetler that the pills could take a long time to work, as long as 14 weeks -- a claim that leads me to believe that the pills were a placebo and that the Shavers hoped that any miscarriage that occurred when the woman was taking the pills would be attributed to their product. Whatever the case, Clarence provided Hostetler with two more boxes of the pills.

When this new round of pills likewise failed to dislodge the fetus, Hostetler went back to Clarence, who told Hostetler to bring Anna to his office so he could "look her over." Clarence told Hostetler, "My mother is a doctor. She has a midwife and a nurse at her home, and we will take Anna to the the house and give her good care."

|

| Dr. Eva Shaver's home |

Shaver was tried for Johnson's death and the 1914 abortion death of another patient, Lillie Giovenco. As the date for the Johnson trial approached, witnesses reported death threats. Hostetler found the threats so frightening that he refused to leave police custody, even though re was free to do so, He told police at the inquest that Clarence Shaver had offered him a large sum of money with which he could flee to Canada. Hostetler said that he had truly loved Anna and was not going to leave. The threats had followed. When appearing at court, Marshall was "on the verge of nervous collapse and a physician was called to give him southing medicines." He was placed in a secret location under police guard.

A Strange Crackdown

- "Michigan Girl Is Victim Of Strange Shooting In Chicago," The News-Palladium, May 27, 1915

- "Doctor Will Have to Explain Shooting of Girl," Port Huron (MI) Times-Herald, May 27, 1915

- "Two Held for Girl's Death," Herald-Press, May 28, 1915

- "Ludington Girl Dead; Police Hold Doctor in Chicago," Detroit Free Press, May 28, 1915

- "Ludington Girl Dead, Three Held," St. Joseph (MI) Evening Herald, May 28, 1915

- "Hold Three For Murder Of Miss Anna Johnson," Ludington (MI) Daily News, May 29, 1915

- "Jurors Hold Shavers For Girl Murder," Chicago Daily Tribune, May 29, 1915

- "Maternity Homes in Chicago Face Sweeping Probe," Detroit Free Press, May 31, 1915

- "Death Threat to Hostetler," Chicago Daily Tribune, June 5, 1915

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

May 24, 1879: The Death of an Abandoned Wife

Twenty-year-old Jennie Fouts, separated from her husband, lived behind the First Presbyterian Church on New York Street in Cincinnati. On May 15, she collapsed on the street. When others attended to her, Jennie reported having suffered from a dull, aching pain for several days.

She took to her bed, where she was cared for until the evening of May 19, when she was admitted to City Hospital. There, she vomited a black fluid that tested positive for blood. Since this is a symptom of the yellow fever, which had killed three people in the previous few weeks, doctors treated her for that ailment.She died on May 24, 1879. After her death authorities made contact with a doctor who had treated Jennie prior to her admission and found her to be suffering from an abortion. She would not divulge the name of her abortionist or of her baby's father.

You state that you are the lawful husband of Jennie Fouts; that you obtained all the facts in relation to her unfortunate death through the Indianapolis papers. You ask: "Was she decently interred?" She was, in Crown Hill. She had some true friends who stood by her to the last, and they should be honored for fidelity to that unfortunate woman. Now, sir, let me thank you for your communication. It only confirms the main points in the verdict rendered at the inquest. .... You communication has completely vindicated the honor of your unfortunate wife. Truth, justice and manhood demand that the world should know all the facts and they must and should be told. I will give you a reasonable time to publish them in your own way.

- "Additional Local News," Cincinnati Enquirer, May 2, 1879

- "Indianapolis," Cincinnati Enquirer, June 10, 1879

Tuesday, May 23, 2023

May 23, 1982: Fatal Embolism?

Life Dynamics lists 29-year-old Rhonda Ruggiero on their "Blackmun Wall" of safe and legal abortion deaths. According to the information LDI put together, Rhonda underwent an abortion in May of 1982. She suddenly died of an abortion-related pulmonary embolism on May 23. An embolism is a flukey thing that can kill regardless of the doctor's skill, so Rhonda probably would have died regardless of whether abortion was legal or not.

May 23, 1985: High-Volume Abortion Mill Screws Up Fatally

Documents indicate that Josefina Garcia, age 37, mother of 2, died after abortion at a Family Planning Associates Medical Group (FPA) facility. Josefina's survivors filed suit against FPA owner Edward Campbell Allred, and 5 other doctors: Kenneth Wright, Leslie S. Orleans, Earl Baxter, Soon Sohn, and Thomas Grubbs. The family said that staff failed to determine that Josefina had an ectopic pregnancy before proceeding with a routine safe and legal abortion procedure by D&C on May 23, 1985. After her abortion, Josefina was left unattended in a recovery room, where she hemorrhaged. She died the day of her abortion. Regardless of whether or not abortion is legal, an ectopic pregnancy is something any abortionist should have diagnosed, if not before the abortion, then certainly after the abortion was completed and there were not pieces of fetus removed. Either way, there was little excuse for failing to detect the ectopic pregnancy. Whether Josefina lived or died would have depended on the state of medicine at the time, and the ordinary skills of doctors who were not abortionists.

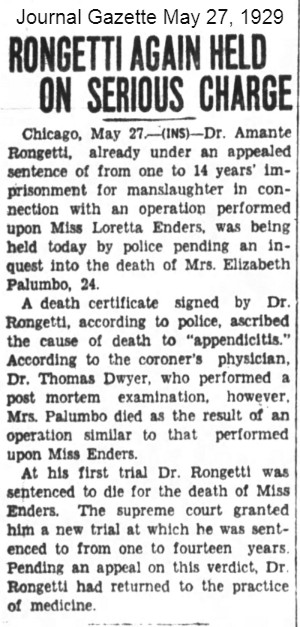

May 23, 1929: A Death While the Doc Was Out on Bail

|

| Dr. Amante Rongetti |

Rongetti was held by the coroner on June 12 for having perpetrated the fatal abortion. When the investigation ended, Rongetti vanished. He turned himself in on July 2 and was released after only a few minutes because he had arranged in advance for his attorney to bail him out.

Rongetti was held by the coroner on June 12 for having perpetrated the fatal abortion. When the investigation ended, Rongetti vanished. He turned himself in on July 2 and was released after only a few minutes because he had arranged in advance for his attorney to bail him out.

Authorities also put West End Hospital under scrutiny, noting that on January 15 of that year the fire prevention engineer had cited ten violations there. The hospital's owner, Dr. Benjamin Breakstone, had himself been investigated by the coroner on other occasions.

Stalling and Acquittal

Rongetti managed to stall the trial for over a year. When the jury was chosen, jurors were required to pledge that if legally appropriate, they would sentence Rongetti to death.

However, he was acquitted after three ballots. The first stood 7 to 5 for acquittal but after three further hours of deliberation the five jurors voting for conviction were won over by the majority.

All of these goings-on surrounding Elizabeth's death took place while Rongetti was out on bail pending a new trial in the abortion death of Loretta Enders, for which he'd been sentenced to die in the electric chair. He won a new trial and Rongetti was found guilty of manslaughter in Loretta's death. He was out on bail in the Enders case when Elizabeth died.

The Medical Board's Verdict

The medical board did not agree with the jury in Elizabeth's case. They moved to revoke Rongetti's license while he was out on bail pending appeal of a manslaughter conviction. Their grounds were that he was under conviction for manslaughter, and that he had committed gross malpractice in the deaths of both Loretta Enders and Elizabeth Palumbo. Rongetti dragged the process out but did eventually lose his license.

Watch Second Death While Out on Bail on YouTube.

Sources:

- "Rongetti Held Again on Serious Charge," Journal Gazette, May 27, 1929

- "Rongetti Faces New Accusation," Decatur (IL) Herald, May 27, 1929

- "Rongetti Arrested Again," The Pantagraph, May 27, 1929

- "Rongetti Again Faces Death Charge," Chicago Times, May 27, 1929

- "Rongetti Again Held on Serious Charge," Journal Gazette, May 27, 1929

- "Seize Rongetti; Probe Death of Young Woman," Chicago Daily Tribune, May 27, 1929

- "Officials Start Hospital Probe in Rongetti Case," Chicago Daily Tribune, May 28, 1929

- "Seeking Rongetti on New Murder Charge," Journal Gazette, June 13, 1929

- "Hunt Rongetti; Held to Jury in Woman's Death," Chicago Daily Tribune, June 13, 1929

- "Police Seeking Dr. Rongetti," Chicago Times, June 13, 1929

- "Rongetti Faces Trial Today on Murder Charge," Chicago Daily Tribune, June 17, 1930

- "Pick Four Jurors to Try Rongetti; Deny Delay Plea," Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1929

- "Rongetti Gives Self Up on New Murder Charge," Chicago Daily Tribune, July 3, 1929

- "Rongetti Free Under Bonds on Second Murder Charge," The Pantagraph, July 3, 1929

- "Jurors Acquit Dr. Rongetti in Woman's Death," Chicago Tribune, June 22, 1930

- "State Seeking to Take License From Rongetti," Chicago Tribune, November 13, 1930

- "License Board Hears Rongetti Trial Evidence," Chicago Tribune, November 14, 1930

- "Enjoin Medical Board's Trial of Dr. Rongetti," Chicago Tribune, December 17, 1930

- "Rongetti Loses Plea to Block Ouster Hearing," Chicago Daily Tribune, February 4, 1931

.png)

.jpg)