Today I'll look at deaths in 1986. They count 11 legal and 2 "unknown."

Wednesday, December 31, 2025

CDC 1986

December 31, 1986: Teen Shoved Out the Door to Die

Eighteen-year-old Sylvia Jane Moore underwent a safe and legal abortion at the hands of 50-year-old Arnold Bickham on December 31, 1986 at his Urgent Medical Care Clinic in Chicago.

She was in the second trimester of her pregnancy, but Bickham used a suction technique suitable for a first-trimester pregnancy. After the abortion, Bickham gave Sylvia repeated injections of Demerol because she was reporting severe abdominal cramps.

|

| Grok AI illustration |

Bickham's license was revoked by Illinois in October of 1988 due to Sylvia's death. The medical board had concluded that Bickham had performed the abortion "without adequate support staff and emergency equipment, and failed to recognize symptoms of abdominal bleeding...." He was arrested in September of 1989 for practicing medicine without license, and sentenced to 30 months probation and 2,600 hours of community service in lieu of 6 months jail, in addition to a $10,000 fine.

Bickham's license was revoked by Illinois in October of 1988 due to Sylvia's death. The medical board had concluded that Bickham had performed the abortion "without adequate support staff and emergency equipment, and failed to recognize symptoms of abdominal bleeding...." He was arrested in September of 1989 for practicing medicine without license, and sentenced to 30 months probation and 2,600 hours of community service in lieu of 6 months jail, in addition to a $10,000 fine. - "Doctor charged after woman dies of botched abortion," The Dispatch, February 18, 1987

- "Charges sought against doctor in woman's post-abortion death," Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1987

- "Abortion doctor sued in death," Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1987

- "Hospital to blame in abortion death, doctor's lawyer suggests," Chicago Tribune, February 10, 1988

- "Mother blames doctor in teen abortion death," Chicago Tribune, February 11, 1988

- "Doctor ripped in license hearing," Chicago Tribune, June 15, 1988

- "Abortion doctor loses his license," Chicago Tribune, November 1, 1988

- "Physician loses right to practice," Chicago Tribune, November 1, 1988

- "Former doctor did abortions, state charges," Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1989

- "No charges yet in 1986 death," Chicago Tribune, October 4, 1989

December 31, 1917: Another Deadly Chicago Midwife

On December 31, 1917, 40-year-old homemaker Victoria Chmileuski died in her Chicago home from an abortion perpetrated by Wilhemena Benn, whose profession is given only as "abortion provider," though she was actually a licensed midwife. Benn was acquitted on March 7, 1918.

Benn had been previously charged in the June, 1916 abortion death of Rosie Kawera and the March, 1906 abortion death of Otilia Winker.

Note, please, that with overall public health issues such as doctors not using proper aseptic techniques, lack of access to blood transfusions and antibiotics, and overall poor health to begin with, there was likely little difference between the performance of a legal abortion and illegal practice, and the aftercare for either type of abortion was probably equally unlikely to do the woman much, if any, good.

In fact, due to improvements in addressing these problems, maternal mortality in general (and abortion mortality with it) fell dramatically in the 20th Century, decades before Roe vs. Wade legalized abortion across America.

For more information about early 20th Century abortion mortality, see Abortion Deaths 1910-1919.

For more on pre-legalization abortion, see The Bad Old Days of Abortion

1972-1978: Heart Patient Dies of Internal Bleeding

In the 1970s, many women and girls died from legal abortion in America. One of them was “Blaire Roe,” whose death was reported in a medical journal years later.

Blaire’s story is sad. She had a heart condition known as Eisenmerger’s syndrome. It is highly likely that she was pressured to undergo an abortion because of this. She was eight weeks pregnant when she was put through a sharp curettage (D&C) abortion and surgically sterilized.

Instead of stabilizing Blaire’s condition and preserving her health, the abortion directly killed her. She bled to death internally from her injuries.

The same study documenting Blaire’s death also recorded the death of “Evie Roe,” another Eisenmerger’s patient whose “life-preserving” abortion killed her instead. Even in the 1960s, medical journals reported Eisenmerger’s patients who were pressured to abort but refused and had positive outcomes for both mother and baby. Although Eisenmerger’s and other health conditions warrant additional concern, today’s medical advances make it possible to provide better care to both. Patients with health conditions deserve better than abortion.

December 31, 1975: Sudden Death on New Years Eve

|

| Pilar Carranco |

Her faith in him was sadly misplaced.

The suction machine Scotti used was 8 years old and had never been intended for use on humans. One of its designers testified that the machine was lab equipment, not medical equipment, and lacked safety features to ensure that it could only produce suction, not blow air.

According to Barbara Zappas, Scotti's assistant, after her boss turned on the machine he said that "it sounded strange." As Zappas knelt down to check to see if the bottles on the machine were leaking, "someone said [the patient] was going into convulsions."

Scotti had started the abortion without ensuring that his equipment was working properly.

Zappas testified that she pulled the instruments out of the way while Scotty started chest compressions. She started providing rescue breaths while a receptionist called 911. Ambulance attendants arrived and took over CPR, which they continued on the ride to Dominican Hospital. There, staff took over Pilar's care and worked for 40 minutes to no avail. The young woman was dead.

An autopsy found air emboli in both her heart and in a vein leading from her uterus. Watsonville Hospital pathologist Harlow D Standage said that the emboli were the obvious cause of her death.

A pathologist testified that the machine being hooked up backwards is the most likely explanation for the air in Pilar's body, but another doctor concurred that it's the most likely explanation, but he also would have expected to see "a lot more air" in Pilar's body if the machine was the issue.

Scotti's defense strategy was to shift blame for Pilar's death from his carelessness to the actions of emergency room staff. His attorney questioned them on the stand about whether they had turned Pilar onto her left side and attempted to drain the air from her heart, which, the attorney said, was "a recommended procedure for treatment of an air embolism."

Scotti himself took the stand during his trial and accused the District Attorney with sensationalizing the case. He countered testimony by several witnesses in the hospital who said Scotti had admitted that he had "blown out" Pilar's uterus.

His testimony was internally inconsistent. He said that he had put his thumb over the end of the canula and felt suction before inserting it into Pilar's uterus. But after he had inserted it, "I wasn't getting any tissue back. I turned around or said to Barbara,' I think there may be a leak around the plug. Check the system for leaks.'"

It was at that point, Scotti said, that Pilar went into convulsions and he started emergency measures.

After leaving the hospital, Scotti said, he went back to check the machine and it was indeed providing suction.

In spite of saying that he had checked the machine before starting the abortion, Scotti also admitted that he'd told the ER doctor that he might have hooked the machine up backwards. One must wonder why he would say that if he had indeed been so certain that it had been producing suction.

Scotti testified that as doctors were fighting to save his patient, he "walked away and prayed." After Pilar was declared dead, Scotti said, a woman he described as "a sister" came to him and comforted him, saying that patients die sometimes and it wasn't his fault. "She was like a message from God."

Scotti's attorney also asked expert witnesses if other activities -- such as yoga, squeezing her legs together, or douching -- could have caused the fatal embolism. The doctor said no, but when asked about "oral copulation" he said he had read of some danger from this activity.

The attorney also argued that the autopsy was not done properly and didn't check for other causes of death such as an allergic reaction to the xylocaine used for anesthesia during the abortion.

Dr. James Weston, a teaching pathologist from the University of New Mexico testified that if the machine had been hooked up backwards, Pilar's uterus and heart would have been distended, and there would have been a large amount of frothy blood rather than two air bubbles. Those air bubbles, this pathologist held, could have been caused by the autopsy. the 50 to 100 cc of air in her heart could have been caused by other reasons. This pathologist also asserted that the original autopsy had not examined Pilar's brain and thus failed to rule out possible other causes of death.

The 7-woman 5-man jury listened to eight days of testimony in the manslaughter trial before retiring. After 4 1/2 hours of deliberation the they were deadlocked eight to four. The judge expressed frustration that they announced their were deadlocked after such a short time of deliberation. The foreman said that the split came on the third ballot, and "We have the opinion it will not change."

They deliberated another hour then were sent home for the weekend.

Pilar's parents, Juan and Carmelita Carranco, sued Scotti.

They were right. The case finally ended in a mistrial but faced additional charges with the medical board, both for Pilar's death and for botching a female circumcision on an adult woman.

Charges dismissed.

The prosecutor argued that Scotti hadn't been double checking when he went back to his office and took the hoses off the machine; he asserted that he was destroying evidence. The defense argued that instead of just taking the tubing off, Scotti would have made sure the tubing was on correctly. The prosecution argued that because embolism was a possible cause of death, the ME took precautions to keep air from entering the heart.

Autopsy found placenta still in place along with a 9 - 10 week fetus.

Scotti's license was revoked by the medical board effective January 30, 1978 on grounds of gross negligence both in Pilar's case and in the case of two adult women who suffered complications from female circumcisions performed by Scotti.

When the judge declared a mistrail, Scotti said he wasn't suprised. Pilar's mother went outside and wept.

HT: killed-by-choice

Sources:

- "Abortion/Death: Charges Filed," Santa Cruz Sentinel, May 10, 1976

- "Parents Sue Dr. Scotti," Santa Cruz Sentinel, June 4, 1976

- "Scotti Defense Opens In Abortion-Death Trial," Santa Cruz Sentinel, July 15, 2096

- "Scotti Superior Court Trial Set Aug. 3," Santa Cruz Sentinel, July 16, 1976

- "Abortion/Death Motion For Dismissal Is Denied," Santa Cruz Sentinel, September 30, 1976

- "The State," Los Angeles Times, March 2, 1977

- "DA Says Machine Wasn't Designed For Abortion Use," Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 2, 1977

- "Machine Not Meant For Use On Humans," Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 3, 1977

- "Cause of Death Cannot Be Established," Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 8, 1977

- "Scotti Charges D. A. With Sensationalism," Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 9, 1977

- "Closing Arguments In Dr. Scotti Trial," Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 11, 1977

- "Scotti Trial Deliberations Resume Monday," Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 13, 1977

- "Scotti Jury Still Has No Decision," Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 14, 1977

- "Jurors Split As Mistrial Is Declared," Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 15, 1977

- "Dr. Scotti Faces Further Charges," Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 16, 1977

- "Scotti Manslaughter Charges Dismissed," Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 17, 1977

- "Doctor said abortion device ran backward, witnesses say," (Torrance, CA) Daily Breeze, March 29, 1977

- "Dr. Scotti License Revoked," Santa Cruz Sentinel, January 10, 1978

Tuesday, December 30, 2025

December 30, 1967: Retroactively Safe and Legal

"Sophia," age 19, traveled from Youngstown, Ohio, to Duquesne, near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on December 27, 1967 to have an abortion performed by 50-year-old Dr. Benjamin King. King also had medical offices in both McKeesport and Homestead.

Sophia was a 19-year-old freshman at Ohio State University. She had gotten King's contact information from her boyfriend, who was also 19 years old. King put out word about his services on college campuses in Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Sophia's boyfriend accompanied her to King's office. They made a down payment of $110 toward the $300 fee for the abortion. (That's over $2,000 in 2020 dollars.) The young couple returned to Youngstown, where Sophia was admitted to South Side Hospital on December 29. She died the following day. King had perforated her cervix, causing both infection and hemorrhage.

Police had Sophia's boyfriend contact King, saying he had the rest of the money. When King came to collect, he was arrested.

- "Cops Say 3rd Abortion Fatal," Pittsburgh Courier, January 13, 1968

- "Doctor Guilty Of Abortion In Fatality," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 12, 1969

- "Doctor Gets 90 Days In Drug Sale," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 15, 1970

- "Abortion Count Brings 1-To-3 Years," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 1, 1970

- "Physician Sentenced For Abortion," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 2, 1970

- "Pa. Court Nullifies Antiabortion Laws," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 30, 1973

Monday, December 29, 2025

December 29, 1971: “Safe and Legal” Coma, Convulsions and Death

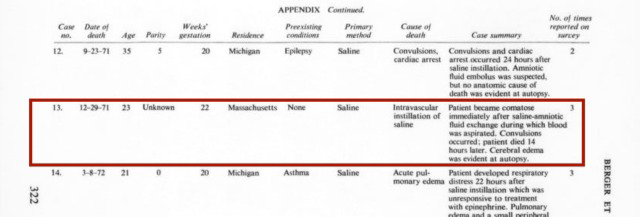

“Beth Roe” was a Massachusetts resident, but she traveled to New York City at 22 weeks pregnant for an abortion that was advertised to her as safe and legal. She had no idea that she would never make it home.

When a toxic concentration of hypertonic saline was injected into Beth’s uterus, blood was aspirated. She became comatose almost immediately. The abortionist had made a fatal mistake and injected the saline fluid directly into her vascular system.

Eight and a half hours after Beth became comatose, she went into convulsions. Fourteen hours after the abortion, she was declared dead. Because of a preventable mistake with a highly dangerous (yet “safe and legal”) procedure, this healthy young woman suffered hypernatremia, cerebral edema, coma and convulsions in her final day of life. She died on December 29, 1971.

Beth was 23 and perfectly healthy. She had no history of any significant medical problems and by all accounts she and her baby should have enjoyed a long life. Sadly, New York’s pre-Roe legalization led to both of their deaths.

"Maternal Mortality Associated With Legal Abortion in New York State: July 1, 1970 - June 30, 1972," Berger, Tietze, Pakter, Katz, Obstetrics and Gynecology, 43:3, March 1974, 325 (See above image for her section of the chart)

December 29, 1971: Antiquated Abortion Method Legal but Unsafe

"Beth" was 23 years old when she traveled from Massachusetts to take advantage of New York's liberalized abortion law in 1971. Beth's doctor chose saline abortion, which is performed by injecting a strong salt solution into the amniotic fluid. The fetus inhales and swallows the fluid, which causes massive internal bleeding and death. The woman then goes into labor.

The abortion was initiated by injecting saline into Beth's uterus. But instead of the amniotic sac, the saline went into Beth's bloodstream. Beth immediately began to have seizures and went into a coma. She was pronounced dead on December 29, 1971.

What is a Saline Abortion?

Saline abortion was hardly a pleasant experience. The abortionist would remove as much amniotic fluid as he could using a needle and syringe. He would then replace the amniotic fluid with a concentrated saline (salt) solution that would poison and kill the fetus. The woman would then go into labor and expel the fetus.

Saline abortion was hardly a pleasant experience. The abortionist would remove as much amniotic fluid as he could using a needle and syringe. He would then replace the amniotic fluid with a concentrated saline (salt) solution that would poison and kill the fetus. The woman would then go into labor and expel the fetus.

Saline abortions became very popular in Japan following WWII. Within the Japanese medical community, however, word quickly spread: this method was unsatisfactory. Too many women were being injured and killed. Over 70 papers were published in the Japanese medical community reporting hazards of saline abortions, including at least 60 maternal deaths. The Japanese Obstetrical and Gynecological Society condemned the technique, and it was quickly abandoned. But the Japanese abortionists kept news of the trouble among themselves -- until Western nations discovered instillation abortions and embraced them with great enthusiasm.

Two Japanese doctors, Takashi Wagatsuma and Yukio Manabe, broke the silence. Wagatsuma wrote, "It is, I think, worthwhile to report its rather disastrous consequences which we experienced in Japan." Manabe wrote, "It is now known that any solution placed within the uterus can be absorbed rather rapidly into the general circulation through the vascular system of the uterus and placenta. Thus any solution used in the uterus for abortion must be absolutely safe even if given by direct intravenous injection. ... A solution deadly to the fetus may be equally toxic and dangerous to the mother. ... In spite of the accumulating undesirable reports, the use of hypertonic saline for abortion is still advocated and used ... in the United States and Great Britain. I would like to call attention to the danger of the method and would predict the further occurrence of deaths until this method is entirely forgotten in these countries."

As western abortionists gained experience with saline abortions, other grim reports arose. A British study published in 1966 found that the saline would enter the mother's bloodstream and cause brain damage. Swedish researchers noticed an unacceptably high rate of complications and deaths. Sweden and the Soviet Union abandoned saline abortion as too dangerous for women in the late 1960s.

For whatever reasons, American abortionists were deaf to these warnings. When New York had completely repealed its abortion law, doctors had tremendous leeway in abortion practice. In New York City in particular, it became popular to inject the woman with the saline in the office, then send her home with instructions to report to a hospital when she went into labor. This was, to say the least, a highly irresponsible way to use an abortion technique that was risky even when performed in a hospital under close medical supervision. Women started dying from these reckless saline abortions.

Other women who died in the pre-Roe days of "safe and legal" New York abortions include:

- Carmen Rodriguez, July, 1970, salt solution intended to kill the fetus accidentally injected into her bloodstream

- Barbara Riley, July, 1970, sickle-cell crisis triggered by abortion recommended by doctor due to her sickle cell disease

- Pearl Schwier, July, 1970, anesthesia complications

- "Amanda" Roe, September, 1970, sent back to her home in Indiana with an untreated hole poked in her uterus

- Maria Ortega, October, 1970, fetus shoved through her uterus into her pelvic cavity then left there

- "Kimberly" Roe, December, 1970, cardiac arrest during abortion

- "Amy" Roe, January, 1971, massive pulmonary embolism

- "Andrea" Roe, January, 1971, overwhelming infection

- "Sandra" Roe, April, 1971, committed suicide due to post-abortion remorse

- "Anita" Roe, May, 1971, bled to death in her home during process of outpatient saline abortion

- Margaret Smith, June 1971, hemorrhage from multiple lacerations during outpatient hysterotomy abortion

- "Annie" Roe,, June, 1971, cardiac arrest during anesthesia

- "Audrey" Roe, July, 1971, cardiac arrest during abortion

- "Vicki" Roe, August, 1971, post-abortion infection

- "April" Roe, August, 1971, death after saline abortion

- "Barbara" Roe, September, 1971, cardiac arrest after saline injection for abortion

- "Tammy" Roe, October, 1971, massive post-abortion infection

- Carole Schaner, October, 1971, hemorrhage from multiple lacerations during outpatient hysterotomy abortion

- "Roseanne" Roe, February, 1971, vomiting with seizures causing pneumonia after saline abortion

- "Connie" Roe, March, 1972, cardiac arrest during abortion

- "Julie" Roe, April, 1972, holes torn in her uterus and bowel

- "Roxanne," May, 1972, convulsions and death at start of abortion

- "Robin" Roe, May, 1972, lingering abortion complications

- Pamela Modugno, May, 1972, air in her bloodstream

- "Maternal Mortality Associated With Legal Abortion in New York State: July 1, 1970 - June 30, 1972," Berger, Tietze, Pakter, Katz, Obstetrics and Gynecology, 43:3, March 1974, 321

- Wagatsuma, "Intraamniotic Injection of Saline for Therapeutic Abortion," Am. Journ. Ob Gyn 11/1/65

- Manabe, "Danger of Hypertonic Saline Induced Abortion," JAMA 12/15/69

- Cameron, "Association of Brain Damage with Therapeutic Abortion Induced by Amniotic Fluid Replacement: Report of Two Cases," British Medical Journal, 4/23/66

December 29, 1977: Safe and Legal in Cleveland

Mary Ann Page was 36 years old when she went into cardiac arrest during an abortion/tubal ligation performed under general anesthesia on December 28, 1977.

Grok AI illustration

Both procedures were completed, then Mary Ann was taken to the Intensive Care Unit at St. Luke's Hospital in Cleveland.

Mary Ann suffered several more cardiac arrests while she was in the ICU. She was pronounced dead on December 29, 1977.

Ohio death records indicate that Mary Ann was Black, divorced, and a resident of Cleveland.

Source: Cuyahoga Co. (OH) Coroner’s Office, Case, 168791

December 29, 1987: Fatal Embolism in Houston

On December 29, 1987, 31-year-old Sheila Watley had a safe, legal abortion at Concerned Women's Center in Houston, Texas. She was 17 weeks pregnant, and had one child. As a black woman, she was both at higher risk of being sold an abortion than a white woman but also a much higher risk of dying once she climbed on the abortion table.

Grok AI illustration

The abortion was performed by Dr. Richard Cunningham. About four minutes into the procedure, Sheila went into cardio-respiratory arrest. She was pronounced dead later that day.

The cause of death was listed as an amniotic fluid embolism, which is when fluid from the uterus gets into the woman's blood stream. From a search on information about Cunningham's license, a lawsuit was filed against him that might have pertained to Sheila's death; the case in question was dismissed, according to information Cunningham gave the Texas medical board.

Source: Harris County (TX) District Court Case # 89-16100; online search of Texas medical board records

December 29, 2003: Fatal Abortion Drugs Courtesy of Planned Parenthood

Hoa Thuy "Vivian" Tran, like Holly Patterson, got abortion drugs at a Planned Parenthood. Vivian was 22 years old, and died December 29, 2003, six days into the abortion process. She‘d been given the drugs on December 23 at the Costa Mesa Planned Parenthood facility. The autopsy showed that she died of sepsis.

Hoa Thuy "Vivian" Tran, like Holly Patterson, got abortion drugs at a Planned Parenthood. Vivian was 22 years old, and died December 29, 2003, six days into the abortion process. She‘d been given the drugs on December 23 at the Costa Mesa Planned Parenthood facility. The autopsy showed that she died of sepsis.

|

| Costa Mesa Planned Parenthood |

Sunday, December 28, 2025

December 28, 1921: Another Mystery in Chicago

On December 28, 1921, 30-year-old housekeeper Belle Keehn died at the Chicago Lying-In Hospital from lung abscesses and septicemia caused by an abortion perpetrated by an unknown doctor on or about November 27.

- Homicide in Chicago Interactive Database

- "Another Victim Points Finger at Dr. Hagenow," Chicago Daily Tribune, January 14, 1922

December 28, 1931: A Self-Induced Abortion in Vermont

According to Vermont death records, 24-year-old Alice E. Kendall of Baltimore, Vermont, attempted to perform an abortion on herself using a catheter in the winter of 1931.

According to the 1930 census, Alice was married to a farmer and they had a toddler daughter and a boarder who lived with them.

Alice developed peritonitis, went into septic shock, and died on December 28.

Watch Vermont, 1931: Fatal Self-Induced Abortion on YouTube.

Saturday, December 27, 2025

CDC 1987

Today I'll look at CDC deaths in 1987. They count 7 legal and 2 illegal.

Their 7:

Case number Age Race Possible Match

496: 15–19 Black Michelle Thames*

497: 35–39 Black Belinda Byrd

498: 25–29 Black Myria McFadden, Kathy Davis

499: 20–24 White Elise Kalat

500: 20–24 Black Patricia King

501: 20–24 Black Patricia King

502: 35–39 Black Brenda Benton, “”

* possible match but unlikely due to data reporting issues

Of course Patricia King is not on there twice, so at least one of those cases is someone else.

(Thank you Kevin Sherlock from The Scarlet Survey for providing this data)

I have 12: 12 legal and 1 possibly illegal, which means that I counted at least four that the CDC missed, but I likely missed an illegal death.